DOJ opinion sparks new debate about legal protections for peyote

Native advocates stand ready to protect decades of religious freedom victories

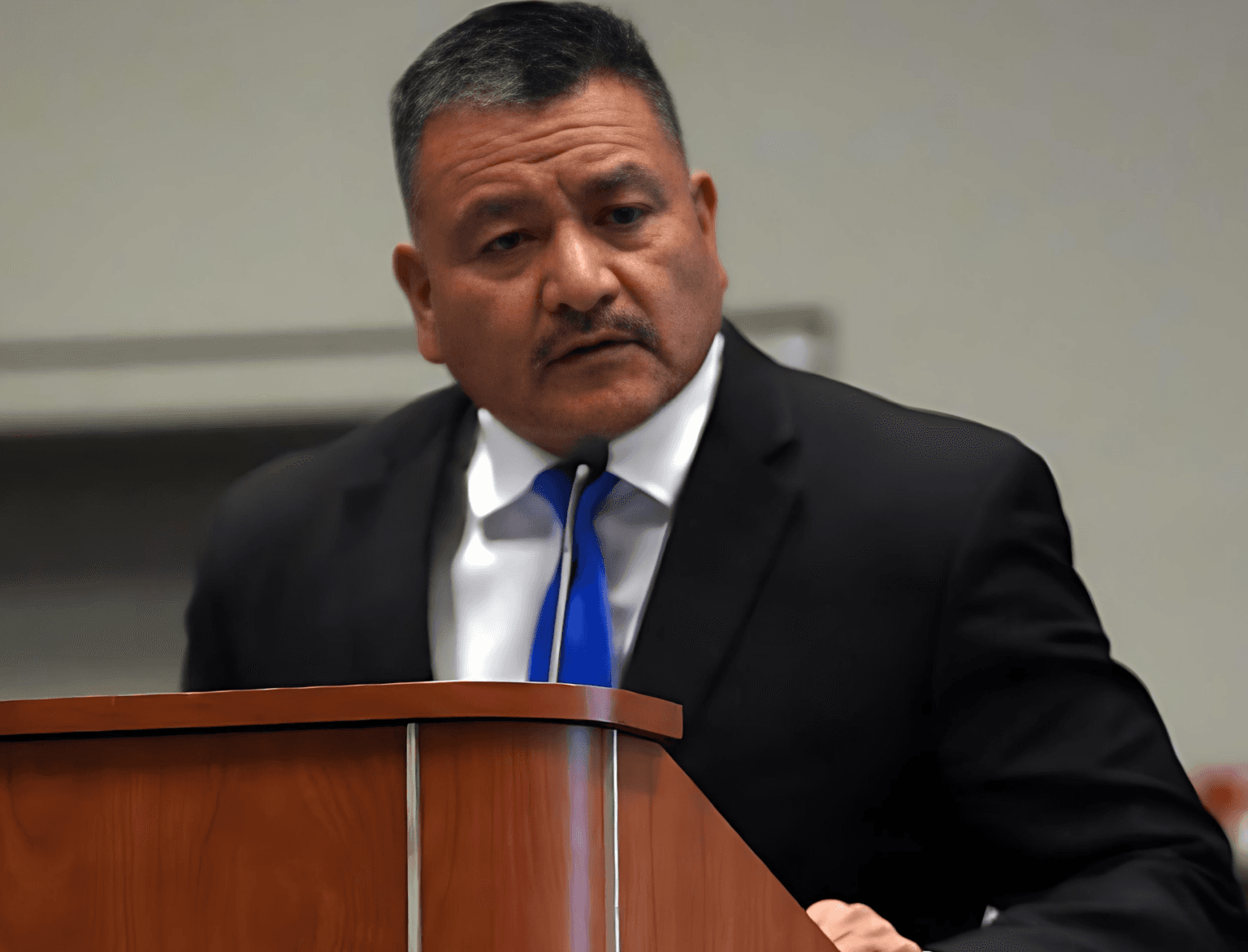

Ryan Sandoval, of the Navajo Nation, speaks about the efforts to decriminalize peyote throughout the country at the National Congress of American Indians Executive Council Winter Session in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 10, 2026. (Buffalo’s Fire/Darren Thompson)

Native American leaders are reacting to a recent Department of Justice opinion that takes aim at congressional protections for the use of peyote, a sacrament used by the Native American Church. The NAC is the only organized religious body in the country whose use of peyote is protected through a 1994 amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

The DOJ memorandum opinion was discussed Feb. 10 by the National Congress of American Indians Peyote Task Force in Washington, D.C. The opinion specifically cites the 1981 “peyote exemption” issued by the Justice Department, which referred to the sacramental use of peyote as “firmly grounded” in NAC’s history. It also acknowledged that exemptions for the use of peyote might one day end up being challenged. Peyote’s traditional use is also mentioned in the 1994 amendment to the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

The DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel issued the Dec. 2 opinion to the Department of Education in response to the federal government’s decision to eliminate race-based programs. In particular, three federal programs specifically fund American Indian, Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian students based on race. The 48-page opinion addresses many aspects of race-based programs in education.

Language in the opinion surprised many Natives, because in addressing education issues the DOJ document also targets protections for the American Indian religious use of peyote. Peyote is a Schedule I drug in the Controlled Substances Act. Native American Church leaders have spent decades fighting to protect the peyote medicine, a sacrament derived from a spineless cactus. American Indian use of peyote predates the U.S. Constitution, and Native advocates have long argued against decriminalizing use of the peyote buttons, which they say could diminish the peyote way of life.

Since the passing of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, peyote has faced many challenges, leading to an amendment of the law in 1994. Changes to the law legalized the possession, transportation and use of peyote for traditional ceremonial purposes by enrolled members of federally recognized tribes. In 1990, a new challenge to AIRFA led to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Employment Division v. Smith. In that decision, the court ruled that states could deny unemployment benefits to Native American Church members fired for peyote use because it is a controlled substance.

The DOJ now proposes a race-based challenge to Natives’ legal right to peyote use. “With respect to these matters, Indians stand on no different footing than do other minorities in our pluralistic society,” according to the department’s most recent opinion.

At the NCAI Peyote Task Force meeting, Greg Smith, a partner at Hobbs Straus, led a discussion of the DOJ legal opinion and emphasized its importance. “When the Office of Legal Counsel issues a legal opinion, that opinion binds every other attorney in the federal government,” he said.

Hobbs Straus is working with other law firms on a rebuttal to the legal opinion and plans to respond to the DOJ in the next several days. “It astounded me that there are references to peyote, and that’s mostly why I’m here speaking,” Smith said.

The Department of Education requested the 48-page opinion, according to Smith, and until it was published, Native leaders had no idea it would cite federal Indian law or the peyote exemption.

According to the 1981 DOJ opinion on peyote exemption, “An exemption for peyote use by the NAC would not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment if the NAC had a constitutional right under the Free Exercise Clause to use peyote for religious purposes.”

“This memo says the only religion out there that used peyote is the Native American Church, so we don’t have to worry about this issue. But today, we do,” Smith said.

What’s changed is that other groups have come forward and said they want an exemption for peyote use too.

Over the last five years, the Native American Church of North America has been leading discussions in Washington and throughout the country on protecting peyote, both in its natural habitat and in the enforcement of its usage. At the same time, there have been efforts by state and local governments to decriminalize mescaline, which is the active ingredient in peyote, for its mental health benefits. It is considered non-addictive like other Schedule I drugs.

But tribal and ceremonial leaders have opposed these efforts, saying that the decriminalization would lead to commercialization and overharvesting of the plant, similar to the saga of California sage, which anyone can purchase on Amazon.

In 2021, NCAI passed a resolution, led by the Peyote Task Force, opposing legalizing and decriminalizing peyote or any of its forms. In 2023, the Peyote Task Force passed another resolution supporting the creation of a White House Initiative Office to protect and preserve American Indian and Alaskan Native ceremonial freedom.

“The Native American Church has opposed broad peyote decriminalization efforts because many of those efforts do not protect the ceremonial, cultural, and ecological realities of peyote and Native tribes and communities who depend on it,” Native American Church of North America President Jon “Poncho” Brady told Buffalo’s Fire. “Decriminalization often treats peyote like other psychedelic substances, which many of our people see as culturally inappropriate.”

Peyote still faces many challenges. While the use and possession of the plant is protected for enrolled tribal citizens, its natural environment is not. Climate change, development and overharvesting have contributed to a shortage of peyote, say practitioners.

“If peyote becomes legal for everyone, it would mean the government would say our exemption for peyote is no longer protected, and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act means nothing,” Brady said. “All of our elders’ efforts would just be thrown out the door and that would be a sad day.”

The natural habitat of peyote is in southern Texas, and it grows only on private land. Harvesting it requires a permit from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Peyoteros, licensed harvesters, collect the buttons on top of the cacti and then sell them by the burlap bag to enrolled members of federally recognized tribes.

The Native American Church of North America, which was formally incorporated in Oklahoma in 1918 as a religious organization, has been meeting with federal officials and congressional representatives for years, asking for a pilot program within the Department of the Interior to incentivize private land owners to preserve lands where peyote grows naturally. While there have been meetings, there is hesitancy about the free exercise clause, given that federal funding could be seen as supporting a religion.

Because tribes exercise political sovereignty and maintain a government-to-government relationship with the federal government, the voices of federally recognized tribes carry the weight of tribal members. NACNA leaders have advocated for tribes to pass resolutions at tribal councils, and over the past five years, several tribes have passed resolutions supporting NACNA and its efforts to oppose the decriminalization of peyote.

They include the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nations, the Oglala Sioux Tribe, Shoshone Bannock Tribes and Northern Arapaho. Other tribal organizations support their efforts as well, including the Coalition of Large Tribes, United Tribes of North Dakota, Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association, Great Lakes Intertribal Council, the United Indian Nations of Oklahoma, and the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians.

Durrell Cooper, chairman of the Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, told the NCAI task force members that his tribal council recently passed a resolution supporting NACNA’s efforts to oppose the decriminalization of mescaline. “There’s some people that agree with it, and some people who don’t,” he said. “I’m always going to be an advocate for this medicine.”

At the task force meeting, Ryan Sandoval, a Navajo Nation citizen and a U.S. Marine Corps veteran, spoke of decriminalization efforts in some states as well as the growing psychedelic movement.

Sandoval attended the Psychedelic Science conference, organized by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, in Denver last year. He and others from the Council of Peyote Way of Life Coalition observed that non-Native conference participants were offered to take a psychedelic trip ingesting psilocybin mushrooms with the peyote sacrament.

In the next several days, advocates who support the legal rights of Native Americans will work on a response to the DOJ opinion because it addresses much more than peyote. The memo questions Congress’s trust and treaty obligations to all tribes.

“We can’t send over a legal memo to the Department of Justice rebutting everything or it’ll go straight into the shredder,” Smith said. “They don’t care, because this is a political document for them too. It was written with a goal in mind. They already knew the answer to the question before they began the research.”

Peyote Exemption for Native American Church, Memorandum Opinion for the Chief Counsel, Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel, Dec. 22, 1981

Constitutionality of Race-Based Department of Education Programs, Department of Justice, Office of Legal Services, Dec. 2, 2025

American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978

1994 amendment to the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act, Aug. 8, 1994

Darren Thompson

(Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe)Reporter

Sharing Is Caring

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.

The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.