Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources map shows reported spills remediated and still under remediation in a 7.5 mile circumference of Wharf Gold Mine near Lead, South Dakota in the northern Black Hills. Photo credit/ Courtesy of SD DANR’s interactive tool

When federal agencies responded positively in 2023 to citizen pleas to prevent a “modern gold rush” in the fabled Black Hills, it was a milestone for a decades-long grassroots movement defending the region’s habitat from looming mega-mining. Tribal and nonprofit organizations celebrated with a December appreciation dinner after mounting a successful public pressure campaign to protect water.

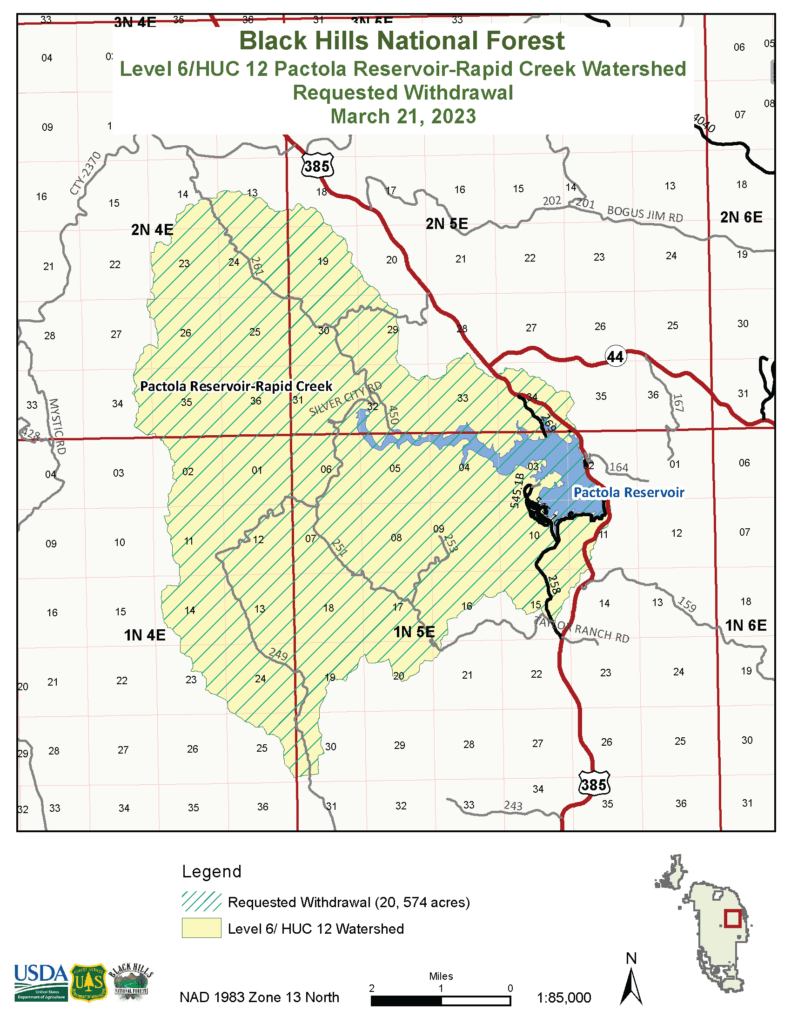

The USDA Forest Service in March proposed a halt to mining claims and exploration on more than 20,500 acres under public jurisdiction. It was a response to a barrage of comments on gold prospecting applications. The tract is about 10% of the Rapid Creek drainage upstream from South Dakota’s second-largest urban area, Rapid City. If the BLM agrees, this important water source will be off-limits to new mining development for at least 20 years.

“Getting to the Forest Service’s proposal took five or six years of hard, focused work involving a broad alliance,” Black Hills Clean Water Alliance Executive Director Lilias Jarding told Buffalo’s Fire. “Longer than that, if you consider that the alliance had been under construction since the 1970s,” she said.

The Forest Service proposal was a departure from the government’s standard operating procedure of granting permits for any mineral exploitation using the premise of the 1872 General Mining Act.

Land managers from both federal agencies held a 90-day comment period and an April 26 hearing in Rapid City on the proposal they call a mineral claims withdrawal. The resounding turnout demonstrated public awareness was at a crest in the wake of a campaign to fend off the “modern gold rush.”

Vox populi, the people’s voice, was on parade. In the town of about 76,000 people, only two Rapid City hearing participants spoke up to promote mineral interests. The rest of the hundreds who testified were part of the estimated 85% of 11,000 commenters in favor of withdrawing access to mining. Among those in the majority was the region’s largest employer, Ellsworth Air Force Base, which derives its drinking water supply from Rapid Creek.

“It took everyone to get to this point — the tribal governments, citizen activist groups, large and small — local residents, visitors, federal employees, and city government,” Jarding said.

“Our hope is just to push the idea that all of the Black Hills is sacred land and important to our people. It all needs to be protected,” Stephen Barrett, Oglala, the alliance’s Indigenous Community Organizer told Buffalo’s Fire.

“For us as Lakota people, we call the Black Hills The Heart of Everything That Is. This is where our origin story is, in Wind Cave. Many of our important ceremonies happen here in the Black Hills,” Barrett said. “Black Elk’s Peak, Pe’ Sla, Bear Butte – there are all these different places – that are just so important for us here. Our whole society revolves around the Black Hills. It’s more than just a plot of land to us. It’s a relative itself. It’s alive. It’s our family.”

Hearing Opens Pandora’s Box

Ever since the gold rush of the late 19th century, mining has played a historic role in the Black Hills. Praising the Land of Gold and Glory has come to be a part of the tourist industry, the top economic activity. So, shifting public opinion has been a challenge for those who seek to maintain the integrity of this unique natural landscape.

Native rights advocates are working to rein in the industry’s environmental destruction by requesting a return of the land stolen in violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Water protectors are trying to harness the impending mining boom through reform of the 1872 General Mining Act. But their efforts are slow-moving.

Meanwhile, organizers alerted constituents about comment periods and local hearings. The tactic increased pressure on regulators who face mounting applications for permits to prospect on public lands. “We have to continuously monitor all these different agencies,” Cheyenne River Sioux tribal citizen Carla Rae Marshall said at the December appreciation dinner. A board member of the Black Hills Clean Water Alliance, Marshall said it was the first step in the organization’s call to action for submitting comments to the Forest Service.

Twenty-three tribal governments of the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association, Great Plains Tribal Water Alliance and more than two dozen other non-profit organizations united on the mining permit withdrawals.

Their work has become an example for other people facing mega-mining proposals. “We deal with a lot of broader alliances on a national level. We’re asked to give reports, seminars, webinars and all those kinds of things on a regular basis,” Jarding said.

The Forest Service hearing on the Rapid Creek watershed mineral claims ban revealed the efficacy of the multifaceted approach. Even before listening to the input, Deputy Regional Forester Jacque Buchanan said public pressure prompted the agency’s reaction. “It really happened when we were hearing from folks the concerns around cultural resources, natural resources … and that being a water source for Rapid City,” she said at the April hearing.

The Forest Service will return a final proposal for further comments in early 2024, Buchanan said. In response, the Black Hills Clean Water Alliance announced on its website: “Be Prepared to Write Comments on This Proposal.”

Local organizers attracted the attention of the national non-profit American Rivers in 2020 when it designated Rapid Creek one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers, “Mining could devastate Rapid Creek’s clean water, fish and wildlife, and sacred cultural sites,” Chris Williams, senior vice president for conservation at American Rivers, said at the time.

However, Rapid Creek is not the only threatened Black Hills drainage. Many local waterways are impaired by mercury and selenium. Four toxic Superfund sites are the result of water pollution from mining over the past 70 years. The quest for gold has been leaving its mark for more than twice that long.

Intruders Enter Sky Island

Conservation biologists consider the Black Hills a “sky island.” It’s an outcropping of high mountain peaks in a sea of Northern Great Plains tall grass and prairie flatlands. The pine-clad terrain and craggy granite spires in the unique Needles Range reach the highest known point between the Rocky Mountains and the Alps. Although tiny, with an area of only about 100 by 75 miles, it gives rise to streams and lakes that are important Missouri River tributaries that comprise the vast Mississippi Basin watershed.

This secluded rural setting is a haven for bison, cougar, elk, deer, antelope, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, fox and coyotes. Eagles, owls, hawks, wild turkey, ducks, chickadees, migratory birds, prairie dogs, ferrets, and chipmunks are common sights. Beaver and trout dwell in creeks overhung with fragrant blossoming branches. The likes of coneflower and breadroot hold medicine and nutrition underground. Wild grapes, cherries and raspberries lure butterflies and humans.

All are relatives — or Mitakuye Oyasin, as the Lakota say.

This is the Sacred Heart of Everything for the Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires of the Great Sioux Nation, as well as the Cheyenne. Ancestors of the Arapaho, Kiowa, Omaha, Kiowa-Apache and several other Indigenous Peoples frequented this landscape for at least 10,000 years. The Arikara, Assiniboine, Blackfeet, Cree, Crow, Hidatsa, Kootenai, Mandan, Salish, and Shoshone are among the many tribes who share a spiritual connection to the Black Hills.

Prospectors encountered the Lakota during the Black Hills Gold Rush of the late 1800s. Native people had been instructed then that He Sapa, the Black Hills, was so sacred that they were not to live there permanently, according to the book, “Voice of the Eagle Woman: The Black Hills in Native American Mythology.” To the ancient ones, this was “a place open for all to use without fear of attack: a refuge from strife.”

In the heat of 19th-century fervor to spread the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, tribal leaders sought to protect this hallowed ground with the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties. Like other treaties of the time, a central tenet assured that Native inhabitants would keep part of their ancestral land base as long as the streams shall flow and the grasses grow.

By 1872, miners intruded into the Hills, ignoring treaty rights. Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s ensuing expedition, nearly 1,000 strong, officially verified the discovery of gold in the Black Hills. The rush was on, resulting in the theft of Indian land.

From that time on, U.S. government agencies have cited the 1872 General Mining Act as a reason to approve exploration and mining on public land. The 150-year-old law classifies mining as the activity with the highest and best use. Any company or citizen can stake mining claims in federal jurisdiction and has the right to explore or mine without paying federal royalties.

“It’s more than just a plot of land to us. It’s a relative itself. It’s alive. It’s our family.”

Stephen Barrett- Black Hills Clean Water Alliance’s Indigenous Community Organizer

Earthworks, one of several national allies of the Black Hills water protectors’ movement, calls the law archaic. Lobbying for reform, advocates now argue for a mining law that will protect drinking water, give communities a voice in mine permitting decisions that affect them, and hold mining companies responsible for their pollution.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1980 offered Lakota treaty signatories a monetary settlement in the case deemed an unsurpassed “ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings.” Tribal governments refused the offer, adhering to the words of the legendary warrior Crazy Horse: “One does not sell the earth upon which the people walk.”

Those who followed the prospectors into the Hills converted it into a tourist mecca, which today generates annual visitor spending in the region of more than $1.1 billion. The USDA Forest Service jurisdiction provides tourists with 1.2 million acres “open, free of charge, for your use and enjoyment,” as the Black Hills National Forest management likes to put it.

Meanwhile, the federal government has confined Lakota jurisdiction to downstream reservation lands covering a fraction of the territory the tribes’ treaty peacemakers had expected. Dating to the treaty violations, modern-day Native Nations infamously still suffer the worst poverty, housing, employment, health and mortality records of any jurisdiction in the region.

“Mining was the catalyst for the military violence and land grabs that have forced us and the land to our present condition, wherein the United States and the state of South Dakota carry out willful violations of constitutional and tribal treaty rights every single day,” Oglala Lakota citizen Taylor Gunhammer recently said. A board member of the Black Hills Clean Water Alliance, he spoke at the 2023 Mni Ki Wakan Summit, held in Rapid City and sponsored by international allies.

The old-time prospectors struck pay dirt with the Homestake claims. Mining baron George Hearst later bought the Homestake claims. His operation became the largest and longest-lasting gold mine ever in the Western Hemisphere. Homestake’s wealth had amounted to $2 billion when operations petered out in 2001.

Flash forward: Contamination in the Black Hills

After sacking the riches from the tribal loss of hunting, fishing, gathering and ceremonial resources, Homestake left behind a Superfund site. Its contamination to Whitewood Creek qualified an 18-mile stretch of this upper Missouri tributary for federal emergency cleanup funding.

In 1981 the waterway became a candidate for the National Priority Listing, which provides taxpayer dollars for the worst hazardous waste sites. The Superfund channels money for EPA to take charge of contaminated locations when the polluters don’t.

Arsenic levels found in the waste stream forced the closure of all private wells at homes nearby. Homestake’s successor agreed to help pay for remediation nine years later after the federal government sued the companies for accountability. Barrick Gold Corp., the Canadian partner that took over the liability, built a water processing plant. It also built and maintains the Grizzly Gulch tailings impoundment, posing the threat of dam collapse.

The Whitewood Creek Superfund Site joined the former Edgemont uranium mill and the Riley Pass Abandoned Uranium Mine on the National Priority List in the Black Hills area. Another Superfund site was soon to emerge when the Canadian Brohm Mining Corp. declared bankruptcy just as it was about to lose a settlement dispute over its acid rock drainage from the Gilt Edge Mine in 1992.

The Gilt Edge work targets heavy metals used in modern mining: cyanide, arsenic, chromium III and VI, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, selenium, silver, thallium, and zinc. About $140 million of public money has been spent to capture this hazardous runoff from the abandoned open pit mountain-top removal mine at Gilt Edge. The pit generates approximately 95 million gallons of poisonous acid rock drainage a year, and no end to the remediation is in view.

Citing budget limitations, EPA denies citizens’ petitions for the cleanup of some 300 more unreclaimed mines and prospects. These old “legacy” stakes leach radioactive contaminants into the Missouri’s tributary Cheyenne River, as well as groundwater tables, according to the Report on Water Tests for Radioactive Contamination. The non-profit Defenders of the Black Hills released the report based on scientist-led citizen monitoring.

Meanwhile, the only working large-scale gold mine in the state, Wharf Mine, has registered 216 “accidental” spills at its open pit mountaintop removal locations from 1983 to 2023, according to the state. That is 5.4 toxic leaks a year averaged over the life so far of the cyanide heap-leaching operation. In multiple accident reports, the mine operators did not record the discharge volumes authorities requested be submitted, according to testimony offered in a 2023 case contesting a Wharf expansion application.

In addition, The state permits the mine to discharge water pollutants in amounts larger than EPA recommendations. Wharf Mine dumps selenium, nitrates, ammonia, coliforms, and cyanide into False Bottom Creek and other drinking water and fishing sources. Chicago-based Coeur Mining Co. plans to expand operations at the Wharf Mine and adjacent property through 2029.

Mining promoters promise they will clean up the past spoils — if only they can do it while they undertake new projects. Agnico Eagle Corp. is eyeing the chance to remine at Gilt Edge. Another company, Dakota Gold Corp., is digging into properties historically in Barrick’s portfolio.

Patrick Malone, chief sustainability officer of Dakota Gold Corp., recently showcased this approach in a local press club presentation. “By going into these previously historically disturbed areas it gives us a chance to fix things,” said Malone “We can address existing concerns. That’s going to cost money. Is it going to come from the taxpayers or is it going to be coming from new projects like us where we can incorporate these things into our mine plans?”

Currently, mining and related businesses annually contribute $252 million in labor income and $502 million to state GDP, according to the South Dakota Mineral Industries Association. The group formed in 2022 because “there is a lot of attention on the industry and the negative side of that is being told,” Executive Director Kwinn Neff said. “I think it is very important that the association forms to provide the other side of the story for the industry and what the benefits are to the communities here.”

Dakota Gold Corp. advertises that South Dakota “is a safe low-cost jurisdiction with a pro-mining government that supports responsible mine development and permitted exploration.”

Critics doubt the state and company have committed to “responsible” mining because state regulators set Dakota Gold Corp.’s liability bond at a one-time fee of $20,000 for drilling on dozens of tracts covering 46,000 acres of claims in Lawrence County.

Dakota Gold Corp. obtained more than 2,000 acres in the Maitland Gold Project from Barrick, the second-largest gold mining operation in the world. For the last two years, the project has drawn resident complaints regarding at least 16 drilling sites that bring in heavy truck traffic along the steep winding gravel road between Central City and Spearfish.

Since it is on private property, no public hearings have been required.

Prospecting Proliferates

Mining opponents insist the critical situation be addressed before any more permitting is allowed. They note that in January 2022, five companies had 148,000 acres of the Black Hills under active mining exploration claims. By October 2023, 10 companies had 293,000 acres claimed, nearly doubling their stakes.

An ongoing citizen mapping project led by Mato Ohitika Analytics LLC highlights “the vast extent of potential mining projects, as well as the modern gold rush that threatens Black Hills water, health, wildlife, and our recreation and tourism economy,” the Black Hills Clean Water Alliance said at a news conference in early 2022.

The Forest Service says no public property remains for mining claims in the northern Black Hills. The entire area has already been pocketed by gold companies. The claims cover acreage along both sides of Spearfish Canyon Scenic Byway. The agency has approved a draft permit for Colorado-based Solitario Resource Corp. to drill for gold at 23 sites on about 27,800 acres as part of its Golden Crest Project.

Just downstream on Spearfish Creek, the Spearfish City Council unanimously passed a resolution against it in June and called for an Environmental Impact Statement study. More than 1,000 people have signed a petition calling on Black Hills District Ranger Steve Kozel to require “a complete Environmental Impact Statement before beginning exploratory drilling in the northern Hills.”

In the petition: “An examination of the Plan of Operations submitted to you reveals Solitario’s threats to every beneficial use of Spearfish Canyon.” The threats include damage to the natural environment, the local economy – which is reliant upon outdoor recreation and tourism – as well as tribal cultural resources, and human, social and physical health.

On Dec. 12, the Forest Service opened a comment period for its draft exploration permit. “Now is our opportunity to object to this plan,” the alliance announced. “We have until January 26, 2024, at 11:59 pm to object.”

It was Minnesota-based F3 Gold LLC’s application for the Jenny Gulch Project that moved the Forest Service to propose a moratorium on new claims, said forester Buchanon. F3 Gold targeted the community of Silver City, S.D. for drilling within a 62-square-mile area.

Breaking Point

The project would take place in a prized recreational location around the inlet to Pactola Reservoir. Its draft permit immediately stirred leaders of the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association to meet with Forest Service brass at U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack’s office in Washington, D.C.

A tribal missive to Vilsack demanded the USDA withdraw “any and all gold mining-related approvals in the Jenny Gulch, including exploratory permits because you have failed to obtain our consent in violation of Articles 2 and 16 of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.”

The treaty “requires consent of the Great Sioux Nation for non-Indians even to be present in our territory, let alone to rape it by mineral extraction. The USDA and the USFS did not ask the Great Sioux Nation for consent on this mine, and you did not obtain it,” the elected tribal leaders’ letter states.

A Lakota warning at a Rapid City Common Council meeting helped prompt a resolution against large-scale upstream gold prospecting. Oglala Lakota tribal member Dennis Yellow Thunder spoke just two days before the Black Hills National Forest closed its comment period on the F3 Jenny Gulch Exploration Drilling Project.

“First of all, let me remind you of the sacredness of the Black Hills,” Yellow Thunder told the council during a Feb. 3, 2020 hearing on the resolution submitted by the Planning and Zoning Committee at the urging of the grassroots organizations.

“Remember what happened the last time gold was discovered? It was the end of our way of life,” he said about the 1800s gold rush that resulted in the Fort Laramie Treaty violations and theft of the Black Hills. The subsequent homesteading and jurisdictional framework imposed on the area abridged the freedom to hunt, fish and worship for the Oceti Sakowin, Seven Council Fires, in their own territories, said Yellow Thunder, who is a Black Hills National Forest Advisory Board member.

“You draw a lot of tourism dollars from these Black Hills. It will be the end of your way of life when it dries up because no one wants to fish or swim or kayak or hunt in these hills because of the contamination that will occur,”

Dennis Yellow Thunder- Oglala Lakota, Black Hills National Forest Advisory Board member

“This time, should this proposed exploratory drilling activity go on, it will be the end of your way of life,” he warned. “You draw a lot of tourism dollars from these Black Hills. It will be the end of your way of life when it dries up because no one wants to fish or swim or kayak or hunt in these hills because of the contamination that will occur,” he said.

“So, think really hard about that and vote in support of this resolution,” he said.

‘Perpetuity Forever’

In April, with the Rapid City claims withdrawal hearing serving as a lightning rod, the Forest Service learned that many constituents want the protected area enlarged and shielded for eternity. Organizers are circulating a petition for an act of Congress to create a larger permanent boundary of the waterway. The draft legislation would be named the Rapid Creek Watershed Recreation Area Act, which would elevate the protection level.

The Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe passed a resolution for funding to save the environment and cultural resources from gold exploration. The resolution calls upon Congress to withdraw the Black Hills National Forest from the scope of the 1872 Mining Act.

A sixth-generation descendant of a treaty negotiator, Reno Red Cloud, who is the Oglala Sioux Tribe Water Resource director, arrived at the withdrawal hearing fresh from another meeting in the nation’s capital with the USDA. “We do support the withdrawal, but we want to do it in perpetuity forever because this is our treaty lands, our homelands. You guys are on sacred ground. We need to have it protected,” he said.

Oglala Lakota citizen Mark Kenneth Tilsen testified: “If we expand this we can protect the waters, so we’re not having to take on these issues one by one anymore. We can get them all. We are slowly transitioning from the idea of management to the idea of stewardship,” he said. “In our Indigenous way, we would say ‘treating the land as a relative.’”

Unci Maka is not a resource to be managed and extracted, said Tilsen, but should be recognized as a “life-giving force.”

“Mining companies rushing into Black Hills,” Black Hills Clean Water Alliance, Feb. 2, 2022

Public comments available at Online Reading Room for USDA Forest Service, Pactola Reservoir-Rapid Creek Watershed Withdrawal

“What Is A Sky Island?” World Atlas

“So Much South Dakota, So Little Time.” https://www.travelsouthdakota.com/

Voice of the Eagle Woman: The Black Hills in Native American Mythology, edited by Linea Sundstrom, photographs by Phillip Henry, Buffalo Bean Books, 2022

“Surviving the ecological impacts of a mining industry that is eager to ravage Hesapa,” Taylor Gunhammer, Black Hills Water Alliance blog, August 2023

“Sacred Lands and Treaty Rights: The Black Hills,” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University

“1872 Mining Law: A century and a half of subsidizing irresponsible mining.” Earthworks

As quoted in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970) by Dee Brown, Ch. 12

2023 Annual Meeting Press Release, Black Hills & Badlands Tourism Association website

“Golden History,” Lead Area Chamber of Commerce website, Lead, S.D.

“Grizzly Gulch tailings impoundment breach would be catastrophic,” Interested Party blog, Aug. 14, 2014

“A more nuclear South Dakota? Stop SCR 601 now!” Black Hills Clean Water Alliance blog, Jan. 25, 2023. https://bhcleanwateralliance.org/2023/01/25/a-more-nuclear-south-dakota-stop-scr-601-now/

The 2022 South Dakota Integrated Report for Surface Water Quality Assessment, South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources, p.73. https://danr.sd.gov/OfficeOfWater/SurfaceWaterQuality/docs

“Newly Formed South Dakota Mineral Industries Association to Educate, Advocate for Mining,” MiningConnection.com. https://miningconnection.com/surface/news/article

Drilling Underway at The Maitland Gold and Richmond Hill Gold Projects, Dakota Gold website, accessed November 2023 https://dakotagoldcorp.com/portfolio/overview/

Gold Mining Threatens the Black Hills – Again! Black Hills Clean Water Alliance blog, Oct. 18, 2023. https://bhcleanwateralliance.org/gold/2/

Talli Nauman

Contributing Editor

Spoken Languages: English, Spanish

Topic Expertise: Climate, Environmental and Social Justice; Right to know; Spearfish, South Dakota

Sharing Is Caring

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.

The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.