Language efforts in MHA Nation are strong but limited by few first speakers

Connecting with the nation’s youth is paramount

Kadin Mills

Special to Buffalo's Fire

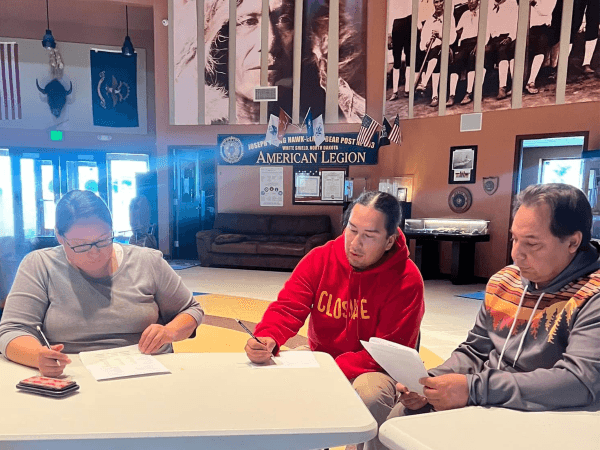

Amber Gwin, Eya Co Nape Fox and Loren White, Jr. learn Sáhniš in a community language class at the Arikara Cultural Center in White Shield, October 2023. (Photo credit: Logan Sutton)

Growing up in White Shield, North Dakota, Red Eagle Woman Perkins connected to her culture through song. Her Grandma Susie taught her to sing in Sáhniš, or the Arikara language, one of three Indigenous languages on the Fort Berthold Reservation. “I really latched on to the songs and I really remembered them,” Perkins said.

Perkins is Arikara, Dakota and Anishinaabe. She was raised in a household that embraced their traditions and languages. But as a kid, she didn’t take the language as seriously as she wishes she had.

“I wish I would’ve noticed how much work my dad was putting in, like when he would try to talk to us in the language,” she said. While she was exposed to the language in elementary school and at home, most of what she retained was from the songs. Now 24, she is making up for lost time.

Perkins currently works as an Arikara language apprentice with the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation’s Culture & Language Department. It’s her job to learn the Sáhniš language and connect with community members and the nation’s youth. Apprentices provide songs and prayers at ceremonies, teach classes and help organize events like the annual Mother Corn Festival at the White Shield School.

Perkins studies the language with linguist Logan Sutton, who has spent much of his career researching it.

Sutton works for the MHA Nation. In addition to helping apprentices learn their languages, he builds language databases and develops materials for all three of the tribes’ languages. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, he also worked with tribal elders to host and record Zoom meetings.

Language efforts at MHA are strong. The Culture & Language department currently offers regular courses in Hidatsa and Sáhniš online and in person, and it is developing new materials for future classes in Nu’eta, the Mandan language. There are also mobile apps for learning Hidatsa and Sáhniš, developed by the The MHA Language Project, an effort of the nation’s education department and Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College. Students across MHA Nation are required to study their Indigenous languages in school, but two main challenges exist: a lack of first-language speakers and a struggle to engage and connect with youth on the reservation.

There are currently no fluent Nu’eta or Sáhniš speakers, and Sutton estimates there are between 30 and 50 fluent Hidatsa speakers. He notes that some people can understand some spoken Sáhniš but may not be fluent. Perkins said there are also few people who know even just a phrase or two in the Sáhniš language.

Bernadine Young Bird is a Hidatsa elder and first-language speaker. She is one of the few whose first language is Hidatsa. “I spoke Hidatsa first before I spoke English,” she said. “I spoke English when I turned five and entered the public school system and had to learn a different language when I went to school. So my experience is very different from the generations after me.”

For more than four decades, she and others have worked tirelessly to preserve their languages for future generations. “For us, our belief is that languages were a gift from our creators,” she said. “Our worldview and our philosophies and our values come from that.”

For Young Bird, the survival of her language means the survival of her people, so she spent her career in federal and tribal education administration. After retiring 16 years ago, she continued to teach Native American Studies at NHS College. Now in her seventies, Young Bird said language revitalization has seen major shifts since she started her work.

“We have great hope to continue our language and hopefully all three languages, but we find it extremely difficult for two of our languages,” she said. “We have first-language speakers for the Hidatsa but none for the Mandan or the Arikara.”

Brad Kroupa described it as “a fight against time.” He is Arikara and began his lifelong language learning journey in his late-teenage years. Now 43, he said the language helped him to connect with his culture. “Learning the language was just always a passion of mine,” Kroupa said, “craving to learn what it meant to be Arikara.”

He earned a doctorate in cultural and social anthropology from Indiana University. There he studied under Douglas Parks, a non-Native linguist who worked with some of the last fluent Arikara speakers beginning in the 1970s. Kroupa said he was the only Native student in the program.

“It was getting to the point where these discussions were happening in tribal communities about not only can we trust these non-Native anthropologists, but where are our own people as historical and cultural knowledge keepers,” he said.

Since its inception, the United States has worked to eradicate Native American languages and lifeways. The federal government provided institutional support for more than 400 boarding schools, including the Fort Stevenson Boarding School and the C. L. Halls’ Congregational Mission Schools — both attended by many children from the Three Affiliated Tribes. Students attending these institutions were forced to speak English instead of their first languages.

Subsequently, many researchers saw an opportunity to exploit what they viewed as vanishing cultures. Many anthropologists and linguists believed the demise of Indigenous lifeways was inevitable, so beginning in the late 19th century they attempted to “salvage” what they could of Native American languages and cultures. Researchers like these often stole ceremonial items from communities and exhumed human remains. Many of these objects and relatives still have not been repatriated, or returned, despite mandates to do so.

The legacy of salvage anthropology has a lasting impact, and Kroupa said the distrust lingers. Even today many tribal communities remain hesitant to work with outsiders. But both Kroupa and Young Bird agree that language conservation needs to keep up with changing times. That includes embracing new technologies and calling on good allies like Sutton.

The youth are the future stakeholders of Indigenous languages, so keeping them interested is paramount. Incorporating technology into language learning could help keep young people engaged with the language. Kroupa saw this firsthand with his own young children, who learned to sing in Sáhniš after watching an animated video of a buffalo that he produced with Sutton.

“They were just so addicted,” he said. “And it worked because they started singing ‘Itsy Bitsy Spider’ in Arikara because they watched that video over and over.”

Texting has also revolutionized the way people communicate. “We already text and communicate in English,” Kroupa said, “why don’t we do that in Arikara or our tribal languages?” Texting in the language is just one way he said he incorporates it into his daily life.

And then there is gaming. “If we want to connect and engage with the youth, we need to start creating words for Xbox, PlayStation, video games,” Kroupa continued.

“Even for sports,” he said. “Our Native youth love basketball, so how do we say ‘bounce pass’ or ‘double dribble’ or these different words in basketball when we don’t have those?” Kroupa coaches basketball and said he calls all of his plays in Sáhniš.

Young Bird recalls the early days of her work, and the resistance she faced from her elders who opposed new approaches to language documentation. “We were kind of open to it,” she said. “My mother’s generation was maybe less open to it. But my grandmother’s — they wouldn’t let us write words down, they wouldn’t let us video tape, they wouldn’t let us record. So if my grandmother were sitting here you wouldn’t have anything!”

Native people in the 21st century are inundated with other worldviews, and Young Bird said it’s important to adapt. “Everything is influencing our people,” she said, “so we have to use our ways and methods to use it for our benefit.” Now that she is an elder herself, she hopes others will be more open to recording their cultural practices and language, before it’s too late.

Kristin Cammorata, Lucero Garcia, Milly Newton, and Ava Whist. Pushing Back against Salvage Anthropology: In Conversation. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. (Spring 2021) https://hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu/pushing-back-against-salvage-anthropology-in-conversation/

Mary Hudetz. ProPublica Updates Its Database of Museums’ and Universities’ Compliance With Federal Repatriation Law. ProPublica (Feb. 25, 2025) https://www.propublica.org/article/native-american-remains-returned-repatriation-nagpra

List of Federal Indian Boarding Schools as of April 1, 2022. Bureau of Indian Affairs. https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/inline-files/appendix_a_b_school_listing_profiles_508.pdf

MHA Nation website: https://www.mhanation.com/history

Native Words, Native Warriors. Chapter 3: Boarding Schools. National Museum of the American Indian. https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/code-talkers/boarding-schools/

Patrick Springer. Voices from the past: Departed tribal elders still talking thanks to computers. Inforum. ( September 19, 2003) https://www.inforum.com/newsmd/voices-from-the-past-departed-tribal-elders-still-talking-thanks-to-computers

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.