By blending tribal regalia with holiday tradition, Indigenous veterans in Oregon are creating a safe, inclusive space where children see themselves in the magic of Christmas.

November is Native American Heritage Month, and North Dakota Indigenous communities are honoring their ancestors, educating their communities and celebrating traditions. As the month kicks off, Buffalo’s Fire asked community members what Native American Heritage Month means to them and how they celebrate the event.

What is Native American Heritage Month?

Presley Heavy Runner of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe said the month serves as a reminder that Native Americans are still here and thriving.

“Native American Heritage Month is a time for me to honor where I come from, my family, traditions and ancestors,” she said.

Standing Rock citizen Ashley Jahner said she uses the month to “honor the sacrifices our elders made for us to be here today” and to educate her community about Native American culture as the director of advocacy for the Sacred Pipe Resource Center.

For Jaimie Archambault from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Native American Heritage Month is more about the harvest season. She said, for her, November is a time to gather with family and prepare for the winter months.

Justin Deegan, Arikara, Oglala and Hunkpapa from the Fort Berthold Reservation, said Native American Heritage Month is about “our resilience, our tenacity and our survival.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 9.6 million people identified as American Indian or Alaska Native in 2020. There are 574 federally recognized Native American tribes and Alaskan Native entities in the United States, and more that aren’t federally recognized, each with their own cultural practices and traditions.

Five tribes are located in North Dakota — the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, the Spirit Lake Tribe, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa and the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate.

Native American Heritage Month has been celebrated every November since 1990, when President George H.W. Bush issued a proclamation designating the month as a time to honor Indigenous contributions to the country and to learn about Indigenous history and culture. Presidents have renewed the proclamation every year, though, one for this year has not yet been issued. President Trump did sign a proclamation announcing November 2020 as Native American Heritage Month during his first term, but his current administration has not announced if they are planning to do so this year.

Several states also officially observe Native American Heritage Month and Indigenous Peoples’ Day, which typically falls on Columbus Day, the second Monday in October.

North Dakota designates the Friday before Columbus Day as First Nations Day, but some tribal citizens are calling for the state to observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead. The state does observe Native American Heritage Month in November. Gov. Kelly Armstrong’s 2025 proclamation encourages North Dakotans “to strengthen the long-standing cooperative relationships” between tribal nations and the state and “work toward a shared future of growth and success.”

For many of the people Buffalo’s Fire spoke to, Native American Heritage Month is a way to educate the larger community about their culture and traditions, but they don’t stop the celebration when the month is up.

Saunders Young Bird, Arikara and Hidatsa on his dad’s side and Hukpapa Lakota on his mom’s, passes down traditional knowledge taught to him by his elders to the next generations as the youth coordinator at Wozu Inc.

“Year round, I continue to practice our cultural ways and ceremonies,” he said.

Why is it important to honor Native American heritage?

For much of United States history, Native Americans could not legally practice their tribal cultures and religions. The United States persecuted Native peoples who participated and danced in cultural ceremonies or practiced traditional medicine, largely under the Code of Indian Offenses of 1883.

And in the 19th and 20th centuries, the U.S. government funded 417 Indian boarding schools designed to assimilate Native American children into Western culture, beginning with the Civilization Act Fund of 1819, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. The coalition counts at least 526 Indian boarding schools in total; often they were church-run. The Peace Policy of 1869 furthered the government’s boarding school agenda; its mission, and the mission of many of these boarding schools, was to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

Children were often forcibly taken from their homes, isolated from their culture and faced abuse, neglect and disease. By 1925, 60,889 Indian children — nearly 83% of those school-aged — were in boarding schools where they were banned from speaking their language and acting in any way that might evoke traditional practices, according to the coalition. Many children never returned home.

Brek Maxon, an enrolled citizen of the Mandan, Arikara and Hidatsa Nation from Standing Rock, said his grandparents would tell him stories about attending boarding school. He said Native American Heritage Month is important for him because it reminds him of the hardships his ancestors endured.

“I like to think about my family, my Native American family. And all of the stories that I remember them telling me, my grandparents especially,” he said. “Whether it was going through boarding school or living through WWII, I mean all of these amazing things our parents and grandparents went through to get us where we are today.”

Some boarding schools were shut down in the 1930s, but decades later federal policies and reports, including the Kennedy Report of 1969 that exposed the abuse Indian children faced at boarding schools, officially led to the closure of Indian boarding schools, though some stayed open through the 80s and 90s.

Around this time, the practice of outlawing Native traditions was also banned when the U.S. Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 — less than 50 years ago — to legally protect Native religious practices and traditions.

For Maxon and other Native families, the trauma their ancestors endured at boarding schools and over years of not being able to publicly express their religions and cultures is still very much alive, only one or two generations removed. Maxon said that’s why “remembering and recalling where we came from” and recognizing Native American heritage is so important.

Justin Deegan, Arikara, Oglala and Hunkpapa from the Fort Berthold Reservation, said Native American Heritage Month is about “our resilience, our tenacity and our survival.”

How is Native American Heritage Month celebrated?

Native Americans in the United States were facing efforts to erase their culture barely 50 years ago. That’s why Ron Lebeau of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate celebrates his heritage every day.

“Native American month to me is helping other people to remember who they are,” he said, which he does as the cultural preservation director at Wozu.

During the month of November, local Native organizations will be hosting events like they do all year long. Though the events might not be specifically for Native American Heritage Month, attending gatherings, ceremonies and events keeps communities connected and culture alive, said Annie High Elk, the director of arts and culture engagement at the Sacred Pipe Resource Center.

High Elk, an enrolled citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, said she personally celebrates her heritage by hiking Bear Butte, a Lakota sacred site located in the Black Hills, South Dakota.

Archambault, who honors November as a time for harvest, said the tradition she practices is picking berries on the Standing Rock Reservation to make traditional medicines. While Jahner said the traditions she holds dear are smudging, praying and being thankful, Heavy Runner said she practices being in community.

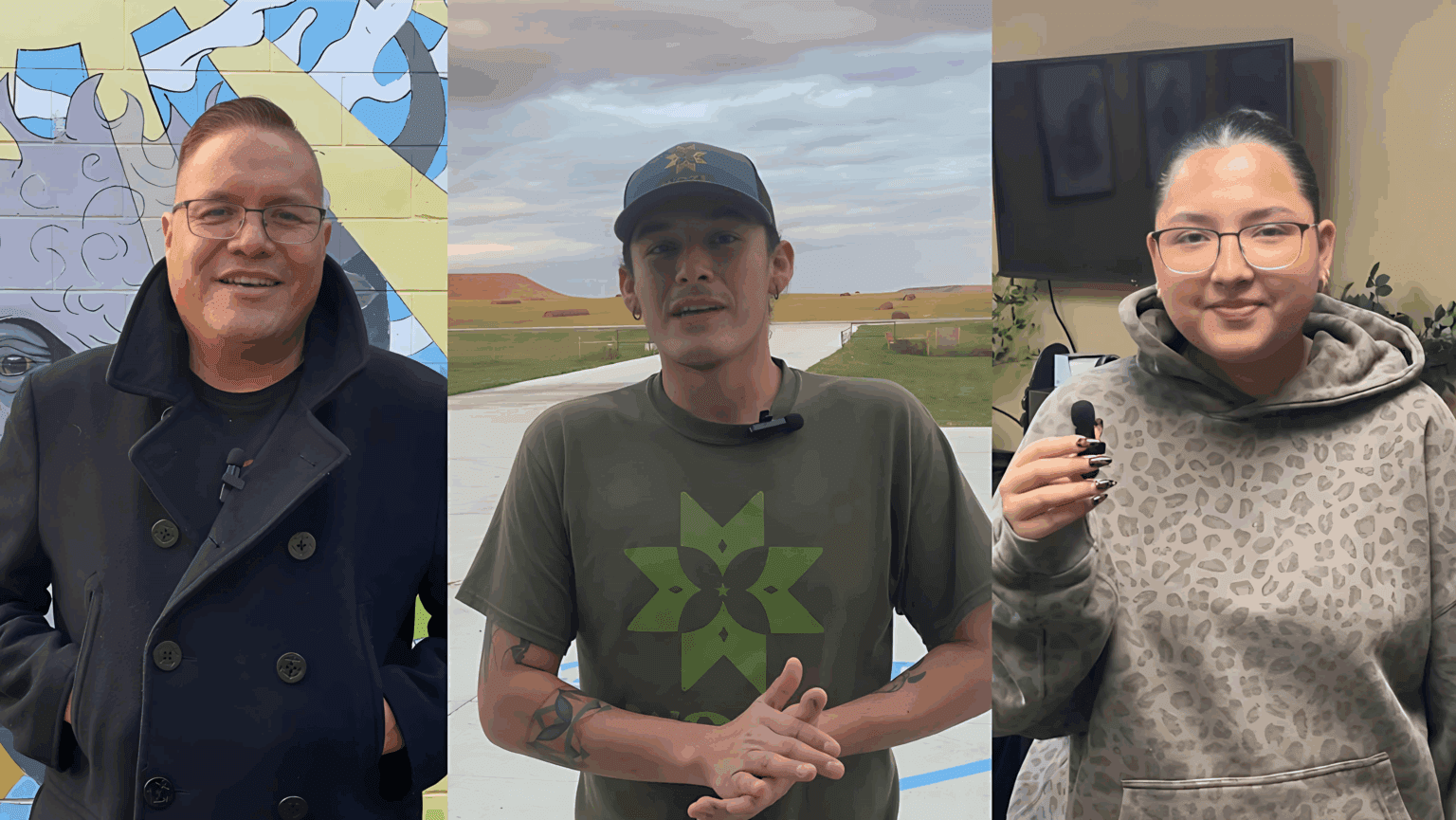

Justin Deegan (Arikara, Oglala and Hunkpapa), Saunders Young Bird (Arikara, Hidatsa and Hunkpapa Lakota) and Presley Heavy Runner (Eastern Shoshone) share what Native American Heritage Month means to them, Oct. 29, 30 and Nov. 3, 2025. (Screen grabs from a Buffalo’s Fire video by Gabrielle Nelson)

Gabrielle Nelson

Report for America corps member and the Environment reporter at Buffalo’s Fire.

Location: Bismarck, North Dakota

See the journalist pageTalking Circle

At Buffalo's Fire we value constructive dialogue that builds an informed Indian Country. To keep this space healthy, moderators will remove:

- Personal attacks or harassment

- Propaganda, spam, or misinformation

- Rants and off-topic proclamations

Let’s keep the fire burning with respect.

Thousands of Natives expected to camp, bring horses, tell stories about Custer’s defeat

Beaders and skin sewers were among the artists selling handmade traditional and contemporary earrings

Through self-determination and support, Native actress rebounds from ICE confrontation

Elaine Miles remembers her friend’s sage advice on being a Hollywood professional

The film tells the story of white buffalo calves on the Turtle Mountain Reservation