Acjachemen Wisdom Day: Honoring Our Ancestors #SaveTrestles

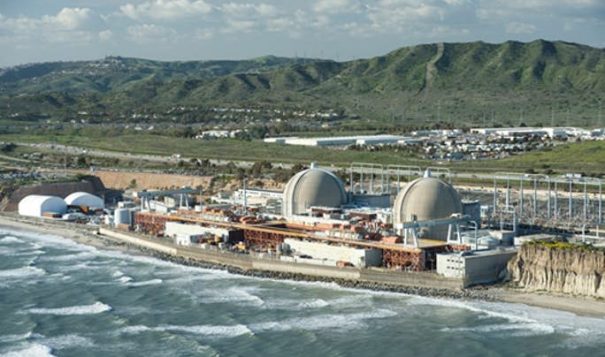

The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) near San Clemente, Calif. Courtesy Southern California Edison

The San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) near San Clemente, Calif. Courtesy Southern California Edison

Twenty seven years ago, a Bechtel engineer named Brock, working for Southern California Edison, discovered a Native American burial site during a construction project at the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS) near San Clemente, Calif.

Brock decided to keep the partial remains of three Native Americans at his home. Upon his death, his wife turned them over to Chairman David Belarde of the Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjachemen Nation at Mission San Juan Capistrano.

The tribe, based at San Juan Capistrano in Orange County, considers itself to have been the steward of the land and ocean around San Onofre for the past 10,000 years. However, since by law, only a federally recognized tribe could accept the remains, they were later transferred to the Pauma Band of Luiseno Mission Indians in North San Diego County for burial.

The burial remains incident is part of a series of complaints that the Juaneno Band of Mission Indians, Acjacheman Nation has against the nuclear plant since its beginning in 1968. Tribal chairwoman Teresa Romero and vice chairman Anthony Vaughn have joined a lawsuit against Southern California Edison filed by Public Watchdogs, to remove nuclear waste from the site.

They claim that Southern California Edison has harmed the tribe because of its “disruptive activities, current unsafe engineering projects and the questionable decommissioning of the San Onofre plant.”

SONGS’s history

The San Onofre facility has been the site of multiple accidents, equipment failures and radioactive leaks until Southern California Edison announced plans to permanently decommission it in 2013.

Desert nuclear dump sites such as Yucca Mounting in Nevada stopped receiving nuclear waste dump material in 2009, however, the San Onofre facility is now slated to receive nuclear waste materials as no other federal waste facilities are currently available, according to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The Acjachemen, along with numerous other groups, strongly oppose a nuclear dump site in close proximity to densely populated areas in Orange and San Diego Counties.

Both Southern California Edison, one of the nation’s largest power facilities, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission insist that the plant is safe. They rule out the chance of an earthquake or tsunami seriously damaging the plant and the deactivated canisters.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission says that the yearly risk for such a quake is 1 in 58,800, but anti-nuclear spokespersons disagree. David Freeman, former head of the Southern California Power Authority said that both SONGS and the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Station near San Luis Obispo, California are “disasters waiting to happen: aging, unreliable reactors sitting near earthquake faults zones on the fragile Pacific Coast, with millions of Californians living nearby.”

Acjachemen Wisdom Day

On June 9, 2018, the tribe celebrated Acjachemen Wisdom Day, co-sponsored by Public Watchdogs, focusing on the tribe’s ancestors and their stewardship of Mother Earth. They made an aerial art display on the San Onofre beach of “Star Man,” consisting of human bodies, members of the Acjacheman Nation, activist groups and local surfers.

Adelia Sandoval, the tribe’s cultural director, explained that “Star Man” originated from the Acjacheman creation story that the tribe descended from the stars. “Star Man is our link with all creation,” she said.

“All the powers that be,” said Sandoval, “including Southern California Edison, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the California Coastal Commission, falsely tell us that everything is going well. We need to stand up together, Natives and non-Natives. We want a safe environment for our children, for future generations, including all of nature, plants, and trees and mountains. If we don’t speak up, who will?”

The Accident

Meanwhile, David Fritch, a SONGS employee and whistleblower, called attention to an accident that occurred at the SONGS facility on Aug. 3, 2018. A 17-foot 49-ton canister with spent nuclear waste got caught on the edge of a guiding ring and nearly plunged 50-feet to the bottom of a silo. “The resultant damage could have caused a large radiation release,” said Fritch.

Southern California Edison acknowledges the mishap on its website, but insists that “at no point during this incident was there a risk to employees or public safety, and immediate lessons learned have already been incorporated into SCE’s processes.”

Radiation Monitoring

Citizen groups want SONGS to allow independent monitors to track the radiation levels at the facility in real time with free public access to its facility. Gene Stone, a geologist and director of Residents Organize for a Safe Environment (ROSE), has begun to monitor the site with state-of-the-art equipment funded by Public Watchdogs with cooperation from Southern California Edison.

According to Public Watchdogs’ Nina Babiarz, “We are proceeding with radiation monitoring whether we have Edison’s permission or not.”

“True, there hasn’t been a tsunami or major earthquake at San Onofre for thousands of years,” Stone added. “But with rising sea temperatures, experts are predicting hurricanes off the California coast in the near future. “Besides, SONGS sits on five earthquake faults. If nuclear plants were being designed today, San Onofre would be on the bottom of the list.”

Stone said there was perhaps a 10-precent chance nuclear waste could eventually be removed, “But only with a public outcry. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has turned all its plants into nuclear dumps with major problems. Their record is abysmal.”

No to Nuclear Waste

The Public Watchdogs lawsuit against Southern California Edison alleges that when Congress that allowed the construction of SONGS it did not permit the storage of nuclear waste at a non-operating facility.

“The threshold in this case is to establish that SONGS continues to cause harm, not only to the Acjachemen people, but to all those who live nearby,” said Charles Langley, director of Public Watchdogs. “We believe the judge has no other choice but to rule in our favor.”

Langley believes that of all the groups protesting against Southern California Edison, the Acjachemen people have suffered more than others from the San Onofre nuclear plant. Moreover, he says that their “sacred activism” comes across more powerfully than traditional protests.

“They believe their prayers are more powerful than atomic weapons,” said Langley. “Tribal chairwoman Teresa Romero told observers on Acjacheman Wisdom Day that ‘Those beautiful cliffs and rolling hills are filled with the bones of our ancestors. We belong to the earth, and the earth belongs to us.’ That is the most eloquent speech I ever heard.”

Southern California Edison Responds to Critics

Southern California Edison spokesperson Liese Mosher declined to answer questions about the lawsuit, stating that Edison does not comment on current litigation. Regarding the eventual disposal of nuclear waste at the SONGS site, Mosher referred to the decommission section on their webpage.

On the site, Southern California Edison commits itself to “transferring used fuel into safe storage and the removal of radioactive components and materials.” The cost of the removal is projected at $4.4 billion. There is no timeline for this removal.

Southern California Edison contends that the current storage of canisters of spent nuclear waste on the San Onofre beach is safe. This is widely-contested by local experts and meteorologists who believe bad weather and earthquakes are a high probability near the SONGS site.

When asked if the storage of Native American remains for 27 years was to prevent, as some charge, delays in construction at the SONGS site, Mosher had no comment. Instead she referred to a document from the U.S. Department of the Interior, which acknowledges that the bones were discovered and eventually re-buried at the U.S. Marine Base, Camp Pendleton in 2017.

The Re-Burial

In the summer of 2017, the human remains of Native Americans recovered during the expansion of SONGS 27 years earlier were re-buried at a quiet ceremony at Camp Pendleton on a hill overlooking the ocean, not far from where they were discovered.

Chris Devers, cultural liaison of the Pauma Band of Luiseno Mission Indians, was there with members of his tribe along with representatives from the Acjachemen Nation. “It wasn’t an elaborate ceremony,” Devers said. “We prepared the remains, put them back to Mother Earth, offered a song and prayers, and reburied them. It was short and sweet.”

S.O.N.G.S. – A Timeline of Hazards, Accidents and Environmental Destruction

1967: San Onofre Unit 1, California’s first large commercial nuclear reactor, begins operating on June 17.

1973: A non-nuclear mechanical failure leads to a 13-week shutdown of the power plant, beginning in October.

1980: The discovery of corroded and leaking heat exchange tubes during routine maintenance leads to a 14-month shutdown for refueling and $67.7 million worth of repairs to the plant’s steam generators

1982 Unit 2 is granted an operating license by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). It begins commercial service in August 1983.

1984: Unit 3 begins commercial operations in April.

1985: A vital cooling system in Unit 1 is crippled on Nov. 21, when five valves fail at once. There are no leaks or injuries.

1988: A California Coastal Commission study finds dramatic declines in marine life near the plant. In July 1991 the Coastal Commission orders an environmental project to compensate for marine damage.

1992: Costs lead to permanent shutdown of Unit 1 on Nov. 30,

2006: Construction begins on an $86 million San Dieguito Lagoon wetland restoration project to make up for environmental damage caused by San Onofre.

2009: On Sept. 26, operators shut down the northern reactor — called Unit 2 —It is taken offline for a planned outage to refuel and replace two 65-foot-tall steam generators. The entire project is projected to cost about $670 million, which is paid for by the plant’s three owners — Southern California Edison, San Diego Gas & Electric and the city of Riverside.

The NRC places San Onofre on “regulatory response,” and orders changes after an investigation reveals staff misconduct and falsified records.

2010: Operators restart the Unit 2 reactor on April 11. Unit 3 is taken offline for generator replacement on Oct. 10.

2012: Unit 2 is shut down for routine refueling and maintenance. A small radiation leak in the Unit 3 on Jan. 31 triggers a complete shutdown of the plant and helps uncover rapid wear on tubing within recently replaced steam generators.

2013: As costs tied to the plant’s shutdown and repairs soar to to $553 million, federal regulators indefinitely delay a decision on whether to approve the restart of Unit 2.

June 7, 2013: Southern California Edison announces it will close the nuclear plant.

Source: San Diego Union Tribune

Mark Day can be reached at mday700@yahoo.com