An Indigenous Adoptee Reclaims Her Culture

Nancy Marie Spears

The Imprint

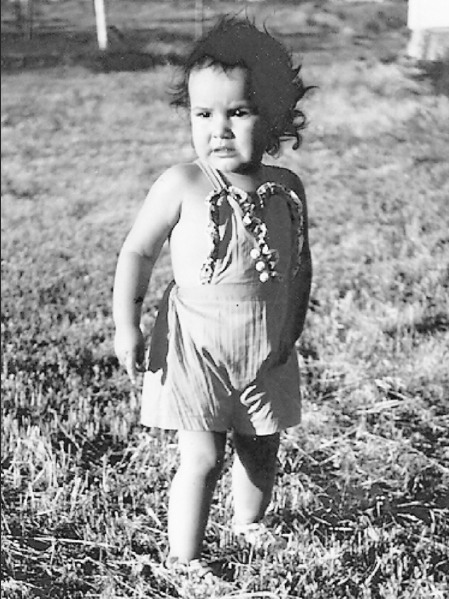

Sandy White Hawk, provided photo

In a new memoir, Sandy White Hawk writes of her abusive adoptive home and how she went on to empower other Native American adoptees to reconnect with their tribal kin.

For years, Sandy White Hawk has been invited to bring the Wabléniča Ceremony to Indigenous communities around the country, welcoming home fellow adoptees taken through adoption and foster care. Using cultural items to “wipe off the smog of shame, sadness, and hurt from the shoulders of all who stand in the circle,” healing can begin, the founder of Minnesota’s First Nations Repatriation Institute writes in a new memoir released Dec. 6.

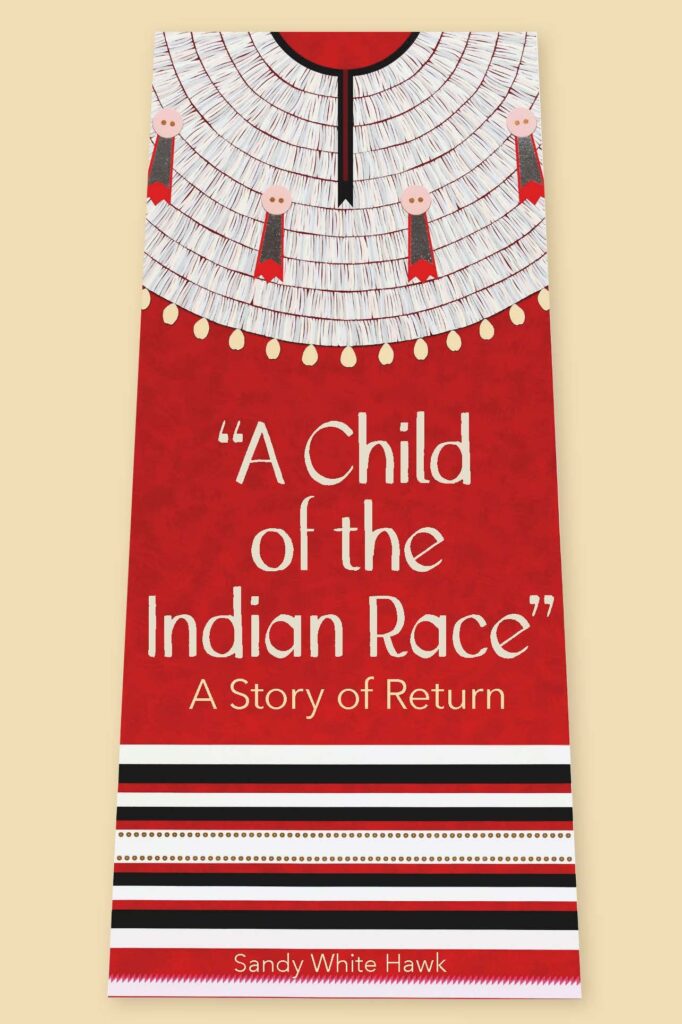

Ceremonies, sweat lodges, and sundances have been key to White Hawk’s own recovery from a traumatic past as a Sicangu Lakota woman, she describes in “A Child of the Indian Race,” published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

“In the Wabléniča Ceremony, we can stand in the circle, open that part of our heart, and let the medicine of smoke from the sage, the sound of the drum, and the song go into that dark place and begin healing,” she writes.

Offering the ceremonies along with Jerry Dearly — an Oglala Lakota songwriter who wrote the Wabléniča song — became more comfortable over time for White Hawk. “It was getting easier to quiet the doubts that fueled my anxieties,” she wrote. “I had started to understand this is what I was supposed to be doing, and I was grateful to be part of this healing time.”

White Hawk, whose Lakota name is “Cokta Najiŋ Wiŋyaŋ, Stands in the Center Woman,” began taking notes for her memoir 20 years ago, she told The Imprint in a series of interviews. Her life story begins with her removal from the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1955.

The book is based on her memories and the scant documents in the adoption file that the woman who raised her passed along before she died. The records show she was taken from her biological mother and adopted by a white missionary couple — a farmer and a housewife — when she was just 18 months old.

In her book, White Hawk, now 69, recounts vivid recollections as early as her toddler years: being lifted into a red pickup truck between “two unfamiliar people,” and “the sour smell of the white arm trying to hold me.” Her next memory was her arrival at the adoptive couple’s home, hiding under the kitchen table as an unfamiliar woman tried to coax her out.

White Hawk does not name her adoptive mother in her book. But she describes her as abusive sexually, verbally and emotionally. Her adoptive mother, she writes, made sure she knew that being a Native child was something to be despised, not celebrated.

From a young age, White Hawk writes she was told she had been rescued from a life of destitution; that her mother was an alcoholic who gave her up and never really wanted her except as a “welfare check so she could drink.” She was “lucky” the white, missionary couple adopted her. They “saved” her from the reservation.

White Hawk said her Native identity became entwined with the hateful words spewed at her throughout childhood: that “I was an ungrateful, dirty, ugly little Indian kid” from a “reservation full of people who didn’t really want me, anyway.”

In the documents finalizing her adoption, a young White Hawk is identified as “a child of the indian race (sic).” That phrase would become the title of her book — which examines through one woman’s life the personal impact of the centuries-long campaign by the U.S. government and Christian church to destroy tribal people and steal their land.

White Hawk described reading that phrase from her adoption files for the first time: “A child of the Indian race — I don’t even know what being Indian meant! I felt ashamed that I didn’t

know what it meant to be Indian. I was so enraged that I was reading about myself as if I were an animal!”

A ‘miracle prayer’

White Hawk was adopted prior to the passage of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which aims to protect tribal children from foster care and adoption into non-tribal homes. She has no record of being in the foster care system, but duly notes that when her care and custody changed hands, there were no legal protections that might have kept her closer to her home on the Rosebud reservation and among her Sicangu Lakota family and culture.

In the decades before the law known as ICWA was passed, as many as one-third of Indigenous children were being removed from their Indigenous communities. “Adoptions were either closed, or there wasn’t due process,” White Hawk said.

White Hawk describes her early childhood separation from her tribe as particularly tragic because she ended up living so close — and yet so far — from her kin. Her adoptive parents originally lived near her reservation, where many of her biological relatives and her mother lived. But they moved from South Dakota to Wisconsin when White Hawk was 4, to give her “a better chance,” in the words of her adoptive mother. Even from a young age, White Hawk recalls, she suspected a deception.

This gaslighting by missionaries who punished her for her Indigeneity became internalized shame, and remained constant through her childhood, White Hawk recounts. She started drinking at age 14 and doing drugs at 16.

By the time she was 28, she had given birth. Motherhood presented the prospect of new wounds.

White Hawk told The Imprint she hit a new low in 1980, when she took her welfare check to a bar, cashed it, and lost five days between Dec. 5 and Dec. 10. It left her daughter without food or Christmas presents.

After that five-day binge in 1980, she whispered a “miracle prayer” to “the Creator,” asking for help in her “compulsion” to drink. And somehow, she said, it worked, shifting something inside her toward change and healing. She hasn’t had a drink since then, White Hawk said.

After that experience, she started attending sobriety meetings two or three times a day, and remains committed to healing the deeper problems that caused her alcohol abuse.

“I had to work to forgive myself, to give myself compassion for not yet knowing how to be a loving mother,” White Hawk said in an interview. “Because how could I? I was never shown that. How could I give what I never had or learned?”

Healing through reconnection

White Hawk was the third-eldest of nine siblings, but had no connection with any of her Lakota relatives or the lands she took her first steps on until age 35. At that time, she gathered all the money she could — just $40 — for her first trip home.

White Hawk’s family on the Rosebud reservation helped her understand her place within the larger framework of genocide towards Native peoples, she explains in her memoir.

They told her stories of other relatives who were also adopted out or taken into foster care, and showed her the devastating legacy of how Indian boarding schools had severed her family. She learned the troubling history of adoptive removals: during the 1950s and 1960s, when white couples couldn’t conceive during the Baby Boom but desperately wanted children, countless Indigenous families lost theirs.

Serving other First Nations adoptees

While witnessing a special at the Rosebud Fair powwow, White Hawk writes of a realization: that while Indigenous communities have ceremonies and songs for nearly everything, no such healing event existed for adoptees. She discussed this with spiritual leaders she trusted during her early years of cultural reclamation, elders esteemed in their communities for their spiritual gifts. As a result, the Wabléniča Ceremony — named after the Lakota word for orphan — is now widely held and offered to adoptees nationwide.

The first Wabléniča ceremony, held in August 2000 in Birch Coulee, Minnesota, began as a four-line song in Lakota. It grew nationwide and continued for 17 years, until the start of the pandemic.

White Hawk’s approach to healing for Native adoptees merges the power of song and ceremony with the expansion of research and data.

In 2012, she created the Minneapolis-based First Nations Repatriation Institute, a first-of-its-kind nonprofit that serves as a resource for Indigenous people who have experienced foster care and adoption, guiding them “to return home, reconnect, and reclaim their identity.”

The institute’s research team published five previous papers on the adoption of Indigenous children that document high rates of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, with a sixth coming as last year’s “American Indian and White Adoptees: Are There Mental Health Differences?”

From her Minneapolis base, White Hawk leads community forums that bring together adoptees, former foster youth and their families, as well as child welfare and mental health professionals who work to prevent the removal of First Nations children. She also initiated an ongoing support group for adoptees and their birth relatives in the Twin Cities area.

In August, the First Nations Repatriation Institute collaborated with the National Native American Boarding Schools Healing Coalition and the University of Minnesota to collect data on the experiences of American Indian survivors of boarding schools, foster care and adoption. Researchers are now examining roughly 1,000 responses to the Child Removal in Native Communities survey.

Mother-daughter bond

The cover of “A Child of the Indian Race” was designed by Dyani White Hawk Polk, 46, her eldest daughter. White Hawk Polk was 4 years old when her mother garnered the strength to pursue sobriety and had begun to find healing through cultural reconnection.

Her mother’s journey inspired the cover image for the memoir. Titled “Wačháŋtognaka | Nurture”, it is one in a series, called “Takes Care Of Them,” of four screen prints depicting Northern Plains style dentalium dresses. The red dress print was inspired by her mother’s red powwow and ceremonial dresses.

Nurturing is one of the infinite ways Indigenous women uplift their communities, White Hawk Polk explained. The color blue on the dress print, Wówahokuŋkiya, depicts the leadership of elders; the yellow, Wókaǧe, is creation, and Nakíčižiŋ, or green, represents the tribe’s ability to protect.

An award-winning visual artist and independent curator, White Hawk Polk has multiple fine arts degrees and has participated in residencies in Australia, Russia and Germany. Her work is featured in museum collections across the U.S., including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Whitney Museum of American Art, Akta Lakota Museum, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and numerous others.

White Hawk Polk describes these pieces as pulling from the continuity of her art, “heavily rooted in porcupine quill work, beadwork, and the art forms that were historically really held up and nurtured by Lakota women.” Each style is inspired by a different time period of traditional Plains-style dentalium shell dresses. Each print is named individually with a quality that expresses how women in Indigenous communities care collectively for children and elders alike.

“All of my older, more formative years, I had a connection to our family, and was growing an increasing connection to cultural practice,” White Hawk Polk said.

The mother-daughter duo now share a home in Shakopee with their husbands, close to numerous other relatives. White Hawk Polk is the mother of two, and named her oldest daughter after her Lakota grandmother, Nina. She attributes her familial and cultural connectivity to her mother’s commitment to reconnection.

“That came directly through her effort to make sure that I didn’t have the same kind of separation she suffered,” White Hawk Polk said. “I’m wildly grateful for the work she’s done.”

This article is being co-published with The Imprint, a national nonprofit news outlet covering child welfare and youth justice.

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.