Crow tribe considers enrollment reset

To combat "death by numbers," Chairman Frank Whiteclay moves to classify all 14,289 current members as full-blooded, so future generations aren't erased by colonial math

James Giago Davies

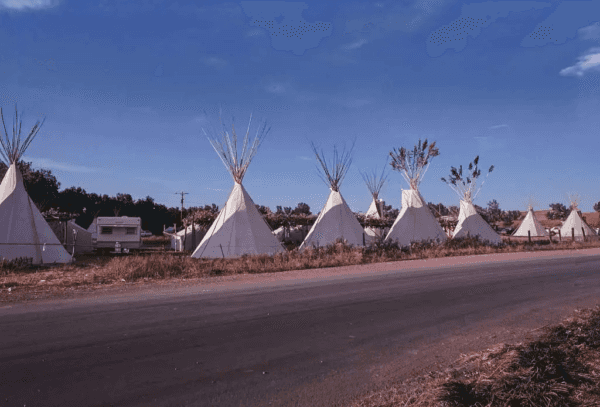

Tipis at Crow Fair (Photo courtesy of Montana Beyond)

Crow Tribal Chairman Frank Whiteclay has introduced legislation that would classify every currently enrolled Crow citizen as “4/4 Crow blood,” a sweeping reset aimed at halting what he and other tribal officials describe as a generational enrollment decline created by the tribe’s existing blood quantum rules.

Under current Crow law, an individual must possess one-quarter Crow blood to enroll. The proposed change would not affect future enrollees directly, but by setting all existing members to full blood, their descendants would inherit much higher blood quantum fractions, dramatically increasing the number of future children eligible for enrollment.

“It will affect all of the reservation in a huge way,” Whiteclay said. The Crow Tribe has 14,289 enrolled members, but tribal leaders say that number has already begun to fall as children born at one-eighth Crow or lower fail to qualify for enrollment.

Blood quantum, a concept introduced by federal authorities and widely adopted by tribes under pressure from the government, assigns a fractional “Indian blood” measurement to each person. It was never a traditional Native system. But its legal consequences are far-reaching— determining citizenship, political rights, access to health care, eligibility for certain college programs, and inheritance of tribal lands.

Experts warn that any tribe using blood quantum faces the same long-term problem: shrinking membership as each generation marries outside the tribe. “Any tribe that uses blood quantum has an expiration date,” said Jill Doerfler, chair of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota Duluth. “That’s what blood quantum is designed to do. Making everyone four-fourths resets the clock. It doesn’t stop it.”

Whiteclay referred to the current system as “death by numbers.” According to tribal records, Crow enrollment has dropped by at least 311 members since 2020, a period during which Whiteclay says the long-term threat has become impossible to ignore.

Crow Secretary Levi Black Eagle said the problem touches nearly every family on the reservation. “There’s a lot of kids and people on the reservation; everything about them is Crow,” he said. “They live here, they’re part of the culture. Everything about them is Crow except their blood quantum by a very small percent.”

Black Eagle noted the personal toll the system takes. His wife, born to a Crow mother and a father from another tribe, was told growing up that she would need to marry someone from a specific tribe to ensure her future children could qualify for enrollment. “It’s sad,” he said. “It narrows how you want to live your life.”

Black Eagle compared blood quantum to livestock classification. “People say, ‘What pedigree does your horse have?’ Or, ‘Does your dog have papers?’ That’s the kind of vein we’re in. But we’re not animals.”

The proposed legislation has been sent to the tribe’s 18-member Legislature and is expected to appear on the January agenda. A committee will review it first, with the full body later voting by simple majority. If approved, the bill returns to the chairman for signature.

“This won’t fix everything,” Black Eagle said. “The United States government requires us to have some sort of metric to say who is a legal member of the tribe. So we’re taking the leeway we have within that system and flexing our sovereignty.”

Whiteclay, who cannot seek reelection due to term limits, said the legislation is meant to “break a cycle of lost enrollment” rather than to solve blood quantum entirely. “The issue is bigger than ourselves,” he said. “We have to have that mentality that the tribe as a whole should benefit, not just a certain few.”

Blood quantum has become increasingly controversial across Indian Country. Opponents say it artificially restricts Native citizenship, fractures families, and accelerates cultural erosion. Supporters argue that expanding enrollment could strain already limited federal resources, particularly in housing, health care, and education.

“Some people think every new citizen drains the nation,” Doerfler said. “Others see more citizens as more power, more votes, more leverage. It depends on how you view citizenship.”

Historically, tribal membership did not depend on blood fractions. Adoption, residency, kinship ties, and participation in community life played larger roles. Blood quantum is a product of federal policy dating back to the 18th century and later used to determine allotment eligibility between 1887 and 1934. In some cases, federal agents arbitrarily assigned fractions to Native people based on superficial physical measurements— a flawed process that still shapes enrollment rolls today.

These inconsistencies are well documented. Doerfler said she has seen biological siblings listed with entirely different blood quantum amounts. “There’s no way to measure blood quantum,” she said. “What test are you going to do—draw blood? It isn’t real.”

The landmark 1978 U.S. Supreme Court case Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez reaffirmed that tribes, not federal courts, determine their own membership rules—even when those rules appear to conflict with individual rights.

The ruling underscored that enrollment decisions are an internal matter of Santa Clara Pueblo, and by extension, all tribal nations. For the Crow Tribe, this means any shift to redefine existing members as 4/4 blood falls squarely within their sovereign authority.

Some tribal nations have begun moving toward lineal descent— membership based on ancestry rather than blood fraction—to avoid the demographic collapse blood quantum is known to produce. But among tribes that rely strictly on fractional requirements, declines are already visible.

Demographic projections prepared for the Crow Tribe indicate that, under the current one-quarter rule, enrollment could fall by more than half over the next two generations. By contrast, resetting all current members to full blood could stabilize population numbers through the century by ensuring their children and grandchildren remain eligible.

While tribal leaders decline to speculate on the long-term impact, the stakes are clear: membership determines not only political power and federal funding, but the cultural survival of the nation.

“There’s a lot of kids here who are Crow in every way except on paper,” Whiteclay said. “We need to decide whether we want the paper to match the people.”

James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. This story was originally published by Native Sun News Today on December 11, 2025.

External

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.