News Article Article pages that do not meet specifications for other Trust Project Type of Work labels and also do not fit within the general news category.

Lower Brule Sioux Tribe claims prejudice, sues county for diluting Native vote

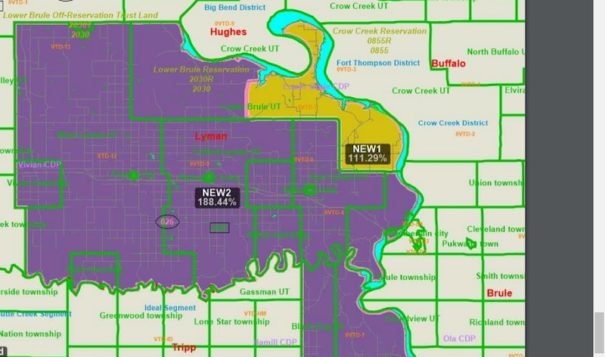

Bounded by the Missouri River on the northeast and the White River on the south, Lyman County has a new 95.6-percent Native voting-age District 1 (gold color) to elect two commissioners from the reservation area. Its new District 2 (purple color) will elect three commissioners.

Bounded by the Missouri River on the northeast and the White River on the south, Lyman County has a new 95.6-percent Native voting-age District 1 (gold color) to elect two commissioners from the reservation area. Its new District 2 (purple color) will elect three commissioners.

The Lower Brule Sioux Tribe recently achieved a majority Native voter district for electing the members of the Lyman County Board of Commissioners. However, the board in place decided not to instate the landmark district in time for the November 2022 election. So, the tribe and several individual members filed a federal Voting Rights Act complaint, which is set for preliminary injunction hearing July 26.

“The board’s decision to delay implementation of its new redistricting plan was adopted with a discriminatory purpose, in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act … and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution,” the plaintiffs contend.

The South Dakota U.S. District Court will decide if the county must apply the new plan in this year’s general election or may delay its rollout. Applying it will assure the potential for tribal members of voting age to seat two candidates of choice in their commission’s new District 1 contest.

A delay by county leaders means this year’s polling remains at-large. It will exclude Lower Brule constituents from full participation in commission races for two election cycles, until 2026. The county claims the delayed implementation is necessary due to “constraints of the current election cycle.”

Daniel McCool, who has a doctorate in political science, said the county’s claim “does not seem credible in an age when district boundary lines can be drawn in a matter of minutes and electoral machinery is computerized.” As a tribal expert witness, McCool noted that Lyman County residents cast 1,617 votes in the 2020 election, “not a huge number of voters to work into a district system.”

No other county in the state has encountered any obstacles to implementation of redistricting plans based on the 2020 Census for the November 2022 election, the complaint said.

Those counties used TotalVote to update the voter registration records of their newly established districts, it said. The software is “easy to use and can be operated by someone with standard office level computer skills.” Dewey, Jackson, Lincoln, and Minnehaha counties already had completed the entire administrative reassignment process by the February statutory deadline.

The U.S. Constitution mandates a national population count every 10 years for the express purpose of adjusting voting district boundaries to reflect demographic shifts and allot public funds fairly. The 2020 Census results launched the most recent legislative redistricting at federal, state, local and hyper-local levels in November 2021.

The census data showed Lyman County’s white population decreased in the last decade, while the Native American population increased by over 21 percent. Tribal representatives met with county authorities to negotiate a district boundary map starting from the release of the decennial statistics in October. They continued meeting until South Dakota counties’ redistricting deadline in February.

The tribal government proposed removal of at-large polling. The tribe offered maps for a system with candidates elected by only residents in each of five single-member districts. This would allow Lower Brule Reservation voters the opportunity to elect two out of five commissioners.

The proposal design would correct an imbalance perceived to result from at-large voting. While tribal citizens make up 47 percent of Lyman County’s 3,718 population, no Native candidate in history has obtained a commission seat. Expert witnesses, submitting voting rights testimony for the court case, conducted a scientific study on the circumstances.

Loren Collingwood and Hannah Walker, both professors with doctorates in political science, revealed corresponding racially polarized voting patterns in the county. Like McCool, both professors are recognized among the top U.S. voting rights specialists. They documented all election results in the county from 2014 through 2020.

“Native preferred candidates disproportionately do not achieve electoral success because the majority of white voters in Lyman County vote as a bloc against the Native preferred candidate. This is true in 25 out of 31 elections (82 percent) under study,” they concluded.

Racially polarized voting constitutes a prime factor that courts should examine in deciding whether at-large or multimember voting districts dilute minority votes or otherwise block minority representation, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee reported during the 1982 reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act.

Nonetheless, the board of commissioners rejected all formal and informal pleas from Lower Brule for five single-member districts. The commissioners ignored a tribal resolution opposing the county lawyer’s hybrid plan. That scheme combined elements of both the at-large and the single-member voting district systems.

The board approved the hybrid map with a District 1, in which two commissioners will be elected at large from an area with a 95.6-percent Native voting-age population. In a District 2, three commissioners will be elected at large from the rest of the county populated mainly by non-Indians.

McCool tagged the plan “highly unusual.” He said he searched for a list of other counties that created “such an unusual hybrid/delayed plan” and could not find any. After the board adopted it, the county’s lawyer wrote the language for a last-minute state law change to legalize it.

Analyzing the plan, however, Collingwood and Walker concluded that “the Native preferred candidate is likely to obtain electoral success in District 1, specifically. Thus, the success rate is 100 percent.” More study would be necessary to determine whether the five single-member district map would be better for parity, they added.

They cautioned that “adopting the hybrid plan this election year is important to facilitating representation for Native American voters at the county level.” The scheme in place to keep the at-large plan in 2022, then to stagger elections between the two districts in the following two election years “will inhibit the ability of Native voters to elect their candidates of choice,” they said. It only allows Native voters to elect a single representative in 2024 and the second representative in 2026 from District 1.

“The board’s decision to delay implementation of its new redistricting plan has the effect of diluting Native American voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,” the tribe charged in the complaint.