News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Supporters gather to discuss Montana ICWA bill

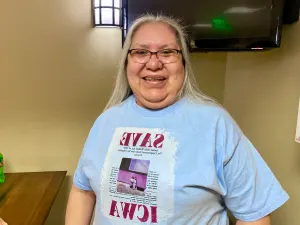

Roberta Duckhead Kittson Nyomo spoke in support of the Montana Indian Child Welfare Act, House Bill 317, on Wednesday, March 22, 2023 in Helena, Montana. (JoVonne Wagner/ICT, Montana Free Press)

Roberta Duckhead Kittson Nyomo spoke in support of the Montana Indian Child Welfare Act, House Bill 317, on Wednesday, March 22, 2023 in Helena, Montana. (JoVonne Wagner/ICT, Montana Free Press)

About 30 people testified in support of the bill, which would solidify ICWA laws in the state

Roberta Duckhead Kittson Nyomo said she and her brother were among the last Native American children adopted out of Thompson Falls before the Federal Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978. The siblings were sent to live with a non-Native family, who Nyomo remembers lacked empathy.

Nyomo, Blackfeet, said she and her brother were abused and she lost her brother to suicide when he was 15.

To this day, Nyomo says she believes their lives would be different, had they been placed in a Native American family. She told her story on Wednesday, following a meeting in which the Senate Public Health and Human Safety committee heard the Montana Indian Child Welfare Act, House Bill 317, which would further reinforce the protections for the state’s Native children by strengthening the tribal involvement in placement options for the state.

“ICWA needs to stay in place,” Nyomo said. “It’s a protection for the younger people of Indian Country and I would never want no Native American child ever to have to go through what I and my brother had to go through.”

The hearing was the last opportunity for public comment on the bill, in which, again, more than 30 individuals came to speak in support, with some of them being Native adoptees speaking from personal experience like Nyomo.

“I would never want no other Indian child to lose their family like I did,” Nyomo said in an interview. “So ICWA is very important to me, and I will do whatever it takes to fight for and keep it in place.”

Many individuals representing Indigenous advocacy groups as well as non-Native speakers came to support HB 317, filling the room. At least nine proponents were present via Zoom call. The meeting lasted nearly three hours and received no public opposition.

The piece of legislation passed through the House Human Services committee and the House floor in February and was re-referred to the listening committee for further debate where the vice chair of the committee expressed his concerns due to his own bill that he said would expand ICWA to all children in the state.

The bill comes as the federal Indian Child Welfare Act is challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court after non-native guardians pursuing the adoption of native children claimed that ICWA was unconstitutional due to racial inequity.

The bill would secure the protections for Indigenous children being removed from their tribe and families through out-of-home placements at the state level.

The federal Indian Child Welfare Act was created in 1978. According to the act, states are required to follow a line of succession when placing children who have been removed from their homes. States must first try to place the children with family members, then with a family of the same tribe living on the same reservation, and finally with a Native American family before placing a child in a non-Native home.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court ruling could pose a threat to tribal sovereignty by taking away tribes’ authority to handle housing placements for tribal children. The Montana Indian Child Welfare Act would reinforce sovereignty protection for Montana’s Native communities.

Rep. Jonathan Windy Boy, D-Box Elder, sponsored the bill and said that he initially wanted to have Montana solidify ICWA into law when he carried a similar bill in a previous session. Now, he believes that there is a greater need to pass the bill.

“Some of you probably heard that there is a federal lawsuit that’s in the U.S. Supreme Court right now,” Windy Boy said during his brief bill introduction last month on the House Floor, citing the case Brackeen v. Haaland. “That may have some ramifications on issues like this.”

If the bill is passed, Montana will join 11 other states who have ICWA policies solidified in state law: New Mexico, Iowa, California, Nebraska, Washington, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Oregon and Oklahoma. Wyoming’s governor recently signed ICWA protections into state law earlier this month.

Sen. Dennis Lenz, R-Billings, sits as the vice chair of the listening committee and also has a bill out in the legislature that is similar to the Montana ICWA bill. Senate Bill 328, sponsored by Lenz is a bill that would apply concepts taken from the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Specifically, Lenz’s bill, which he commonly refers to as the “ICWA For All Bill,” would apply to all of the state’s children. However, instead of focusing on placing children with Native families, Lenz’s bill states the preferred placements would seek to place children with families with similar connections of the child such as ethnic, cultural and religious heritages.

“What I tried to incorporate is, say, for instance, in place of tribal, I put community and family and church and whatever I could to kind of [create] equivalency,” said Lenz in an interview after the meeting. “Some things are not an equivalency on the reservation because they have a different sub-structure of government.”

Lenz also explained why he doesnt think Windy Boy’s bill could coexist with his version, saying that he finds it problematic when taking a federal law and bringing it into a state law. However, Windy Boy and several attorneys say both bills could.

Lenz became emotional during the meeting when it was time for committee questioning. Lenz asked Kelly Driscull, a family defense attorney, questions concerning the differences between the HB 317 and SB 328.

“There are particular experiences that have disproportionately impacted Native American Families undoubtedly,” said Driscoll in response. “We still have almost half of Indian children in the state of Montana subject to (Children and Family Services) investigations and to compare that to non-Native families, White children, only 37 percent of them are subject to CPS investigations.”

Driscoll also added that is still a high number but there are certain experiences of being a Native parent in the state that exposes them differently to non-Native parents and expressed that there should be additional considerations for Indigenous families. She also said that she believes that both Windy Boy’s and Len’s bills can coexist in which Lenz disagreed.

“I’d love for us to coexist but I’d also like for us to live in the same house, not just be neighbors across the fence,” Lenz said.

“That a child is a child, the parents supported and the kids are not falling through the cracks,” said the vice chair while getting emotional. “I don’t, if we move this forward, to then complicate it for every other case out there.”

Windy Boy spoke in his closing statement that there are differences in the state and tribal relationships.

“The difference is history,” said Windy Boy. “There has been a lot of things that have happened over the course of the last hundred years, for example the boarding school era had come about and recently subsided in the ‘70s.”

Windy Boy said that these are the acts that justify the need for higher protections for Indigenous children. He mentioned how post traumatic stress disorder is one of the long lasting effects of the treatment of Native children in history, an outcome that’s related to generational trauma in Indigenous communities and families.

“Maybe something that’s going to improve not just for this bill but for everybody as whole Montanans because that’s what we’re aiming to do is try to protect the best interest of children and that’s what the purpose of this is.” Windy Boy said, referencing his 75-page bill.

Dateline:

HELENA, Montana