The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

Uncovering the history of Rapid City Indian School

Construction set to begin on the Remembering the Children Memorial, to be built on the site of the former boarding school

Amelia Schafer

Rapid City Journal via ICT

Kibbe Brown’s aunt who attended the Rapid City Indian School had saved a panoramic photo of students and staff from between 1925-27, with the school’s campus in the background. (Photo courtesy of Remembering the Children)

WARNING: This story contains disturbing details about residential and boarding schools. If you are in crisis, here is a resource list for trauma responses from the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition in the U.S. In Canada, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

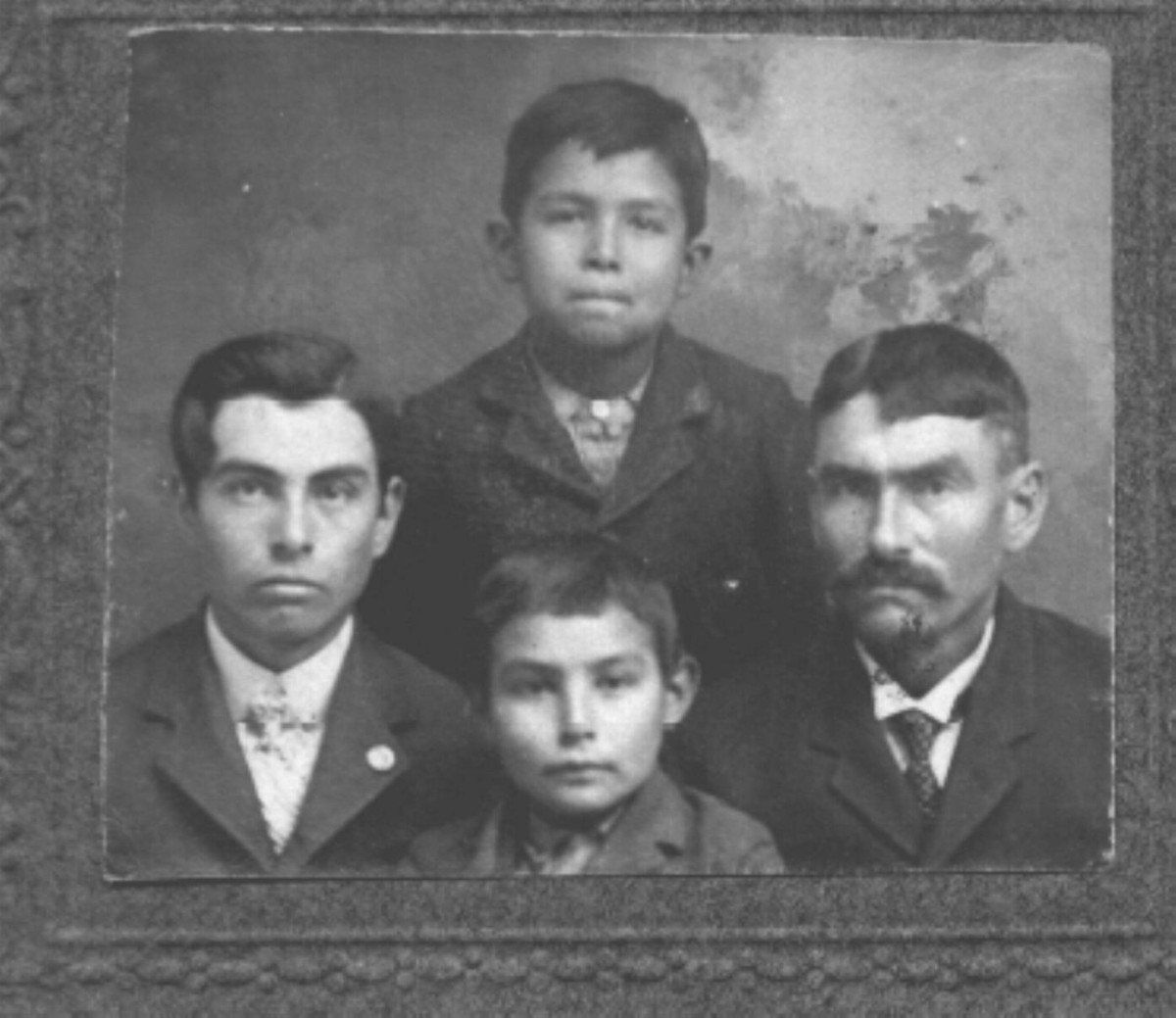

Ben Sherman, Oglala Lakota, comes from a family of boarding school attendees, including himself. Four generations of Shermans attended boarding school starting with his great-great-grandmother Lizzie Glode-Sherman, one of the first students at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. But it wasn’t until he was an adult that he learned about his great-uncle who never came home.

Most of Sherman’s ancestors attended Genoa Indian School in Nebraska. His great-great grandparents met and were married at Genoa. Only one member of the Sherman family, Mark Sherman, attended Rapid City Indian School, a government-operated school that aimed to teach middle school students, but ended up with an age range of 7-19.

Mark Sherman was also the only family member to never come home from school.

“Lizzie gave birth to Mark and lost him to boarding school, which is the sad irony, she lost her son to that system,” Ben Sherman said.

Eighty-eight years after the school’s closing, organizers are working to make sure survivors, victims and descendants aren’t forgotten.

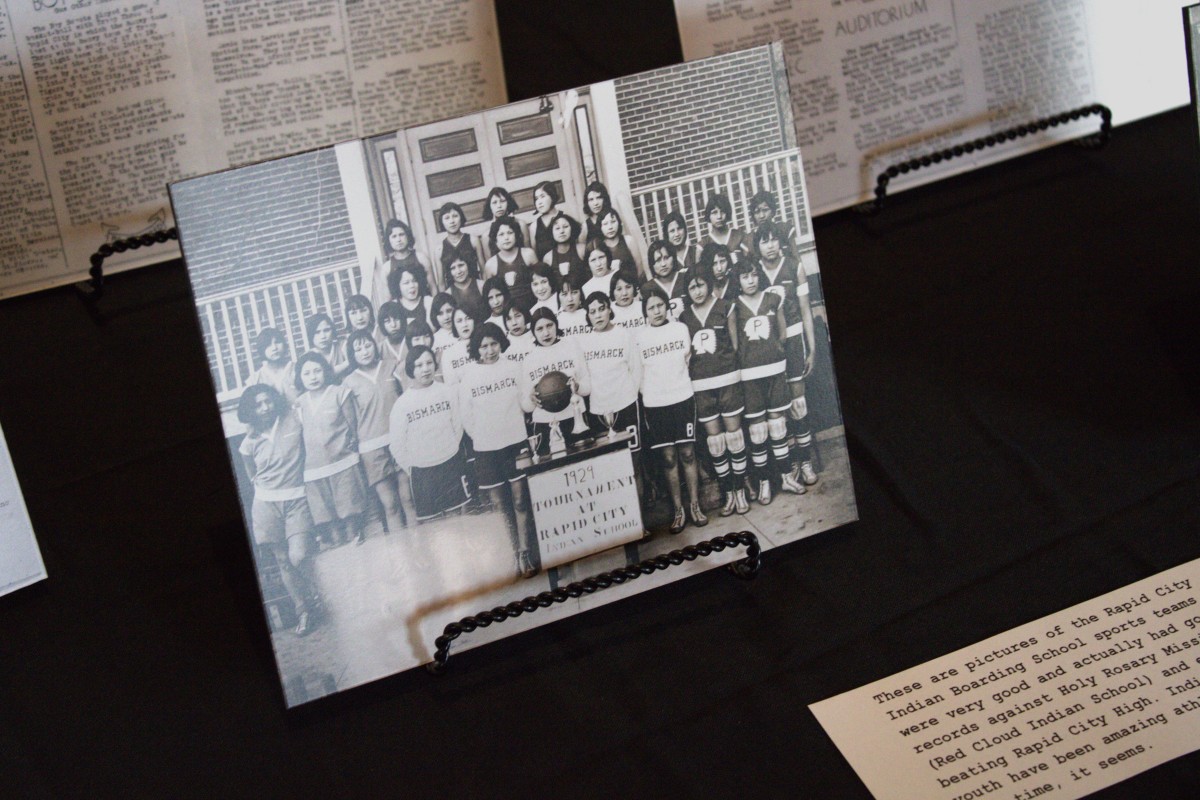

In early 2024, construction will begin on the Remembering the Children Memorial, to be built on the former boarding school grounds. On Sept. 30, the Remembering the Children exhibit opened at the Tusweca Gallery in downtown Rapid City, featuring historical photos and documents from the school.

Life at the Rapid City Indian School

At the Rapid City Indian School, “disobedient” children were locked in jail cells, chained together and made to march for hours, starved, beaten and neglected. Early attendees report meals consisting of boiled beef and bread day after day. Children’s lives were dictated by the bell, they marched to and from class every day, and only spoke English.

Indian agents on reservations would withhold rations until families sent children to school. In some cases, children would be forcibly removed from families.

The school, which was located on the west side of Rapid City, was a 1,200-acre campus with dormitories, farming equipment, barns, root cellars, classrooms and more.

In the school’s 35-year run from 1889 to 1935, approximately 2,089 students attended, according to records from the National Archives. A majority of students (88 percent) were from the Oceti Sakowin (Lakota, Nakota, Dakota), though some were as far as 700 miles from home.

While Ben Sherman’s experience attending the Pine Ridge Boarding School in the 1950s was vastly different from his great-uncle’s, children still struggled with boarding school life.

“One of the worst things about boarding school is that there’s no parentage, there’s no love. When I attended boarding school, that was something I saw,” Ben Sherman said. “It really affected the little guys and the little girls.”

The living conditions at the Rapid City Indian School prompted dozens of students to flee the school, including Mark Sherman.

On October 15, 1910, six Lakota students escaped the Rapid City Indian Boarding School on foot, heading toward Scenic. The boys followed the railroad toward Kadoka, keeping the Black Hills to their right as they headed south toward home, Pine Ridge.

Once the boys finally made it to Scenic, they stopped to rest, sticking by the railroad tracks. Four boys settled down by an embankment while two, James Means and Mark Sherman, lay on the tracks.

All of the boys, too physically and emotionally exhausted to wake up, didn’t notice the oncoming train until it was too late. Sherman, 17, and Means, 15, were struck. Sherman died instantly. Means was taken back to the Rapid City hospital, where he died the next day. His direct family has never been identified by researchers.

Historical trauma in modern life

The impact that boarding schools have on future generations is difficult to quantify. Boarding school survivors often struggled to form healthy relationships, family dynamics and self-image. The traditional Indigenous extended family system was nearly eradicated.

“There have been effects on my family,” Sherman said. “We lost our language and a good part of our culture because of that. We all were required to speak English in boarding schools and there was punishment for not doing so.”

Historical events can impact the mental health of descendants, despite whether descendants know about the event, by causing genetic changes handed down through generations, according to a growing body of research studying epigenetics.

Today, descendants are working to reclaim what was taken during the boarding school era and memorialize the stories of those who didn’t survive, such as the 50 recorded children who died while attending the Rapid City Indian School.

“One thing I’ve learned in this work is that there’s trauma associated with not knowing,” said Amy Sazue, Oglala/Sicangu Lakota and the Remembering the Children executive director, speaking at the Sept. 30 exhibit grand opening. “The idea that we may never know and that we have ancestors, relatives, grandmothers who lost children and never knew where they went.”

Of the deceased, six children and one infant have never been named; however, each of the 50 dead children’s blood quantum (percentage of Indian blood) is stated in detail, which is sometimes the only thing listed on their death record.

Another seven of the children’s graves have never been located: Joseph Face Dakling (surname may be Face Darling or Dark Face), 14, Rosebud; Mary Galligo, 18, Pine Ridge; Josephine Spotted Bear, 17, Standing Rock; Ida Logan, 18, Rosebud; Spencer Ruff, 17, Pine Ridge; Sophia Fleury, 17, Crow Creek; and Abner Kirk, 12, Sisseton.

Most students died from diseases the school was ill-equipped to combat, but several died from unknown or unlisted causes.

Researcher and Advisory Board member Kibbe Brown, Oglala Lakota, had been working at Sioux Sanatorium and preparing for the hospital’s 75th anniversary when an elder asked her what was going to be done about the children’s graves.

“It opened Pandora’s box,” Brown said. “We knew there had been some burials from the school and from the tuberculosis era, so we started asking around.”

With the help of Lakota lawyer Heather Dawn Thompson, the group contacted tribal leaders and helped to compile historical information. Brown and other researchers spoke with relatives who had attended, dug through the archives, and gathered input from spiritual leaders. Brown even learned about her own family’s history.

Brown’s great-uncle, Adolf Russell, died in a boiler room accident at the Rapid City Indian School in 1909 while attending the school. Russell was only 10 years old.

Oral history tells that a starving Russell had taken a potato from the school’s garden and attempted to cook it using the boiler, causing it to explode and kill him.

After Russell’s death, family members were sent to Holy Rosary Mission (Red Cloud) in Pine Ridge, until another family member, Elsie McGaa, died of pneumonia while attending. After McGaa’s death, the children were sent back to Rapid City, where they experienced a more reformed education experience than Russell had.

A majority of paper records pertaining to the school are located in the Kansas City National Archives, but many have been digitized and are now available on the Remembering The Children website, including a searchable list of attendees and known deaths.

But there is still more research to be done. Out of the deaths at the school, two are infants, whom researchers have no idea where they came from.

“There are so many anomalies and so many things we may never know,” Sazue said.

Misspelled and mistranslated names also work against researchers hoping to identify victims. One victim, Joseph Face Darkling, had his name spelled or translated three different ways.

A legacy of boarding schools

At the peak of the boarding school era, 31 schools operated across South Dakota, 11 of which were government-run, including the Rapid City Indian Boarding School.

While the Rapid City Indian Boarding School was government-run, on Sunday students were required to attend church or Sunday school. The nondenominational alternative was run by local Catholic priests.

“The training of character is the most essential part of every student’s education, and this school stresses in every proper way the religious and moral training of the students,” as stated in the school’s 1928 promotional pamphlet.

Students followed a strict military schedule, waking up at 5:30 a.m. and marching around campus. Students’ days were spent alternating between working and schooling, half of the day spent doing each, and the days ended at 6 p.m., with five hours spent working and the other five spent learning.

“My aunt remembers her mother (who attended the school), saying they marched us. Their whole day was governed by the bell, it was part of their strategy of acculturation and it worked,” Brown said.

Most work included general maintenance of the school, including tending to the boiler and steam laundry, but trades such as woodworking and auto repair were occasionally taught.

According to the 1928 promotional materials, “It is not impossible that he (the child) will write you that he is sick; or that the school is not giving him enough to eat; or that he is being abused and not cared for properly… Please assist him by being kind but firm – he will thank you for it someday.”

The material also states to report and return runaway students immediately.

In 1909, over 10 boys ran away in less than a year. During the 35 years the school was in operation, several students attempted to run away. Most were caught relatively quickly, and those caught were punished harshly. Students who ran away were subjected to unpaid labor for the entirety of the summer break, and some were recorded to have been kept in jail cells.

After the school closed in 1935, it was converted into Sioux Sanatarium, a segregated tuberculosis clinic that later became the area’s primary Indian Health Service clinic.

In 2017 discussions began regarding granting two parcels of land back to the community for the construction of a future Indigenous community center, and a future memorial. The rest of the original 1,200 acres where the school sat now belongs to the South Dakota National Guard, West Middle School and several churches.

Advocacy

While Sherman and Russell are buried back home on the Pine Ridge Reservation, many of the graves of children who were buried at the school are unmarked and unclear.

Heavy and prolonged usage of the school’s grounds has made it nearly impossible for ground-penetrating radar to be effective in unearthing hidden graves. Radar is only able to detect underground soil shifts, and the site where graves are suspected to be has been heavily used for over a century.

To honor the victims and survivors, a $2 million memorial site is to be built over a 25-acre plot that used to belong to the school. This 25 acres includes the land where tribal historic preservation officers have identified unmarked grave sites.

The memorial will feature five burial scaffolds, the traditional burial method of the Lakota people, an honor the victims didn’t receive. The memorial grounds will also feature a walking trail, several sweat lodges, and one boulder for each victim. More boulders will be added as more victims are identified.

The Remembering the Children exhibit at Tusweca Gallery will be open until Oct 15. Guests can stop by the gallery from noon to 6 p.m. to view historical information, future memorial plans, and old photographs.

“We’re excited to have an in-person public space for people to look at the things we’ve learned in the last nearly 10 years, and show our plans for the memorial,” Sazue said.

The exhibit also includes research gathered by the Pokagan Potawatomi company 7 Generations Architecture & Engineering, which is involved in the memorial planning process.

Every year since Oct. 2018, community members walk from Sioux Park to the future site of the memorial next to Canyon Lake Methodist Church. A sign with the name of each child who died is held by a walker, usually a member of the victim’s family.

Oglala spiritual leader Gwen Hollow Horn inspired the walk. After walking the grounds, Hollow Horn told researchers some of the children’s spirits were still on the grounds, and all they wanted was to be remembered.

“I feel really good about how far we’ve come,” Brown said. “The memorial walk helps our community to build healing.”

The physical memorial is currently undergoing an environmental impact survey and should be completed before the 2024 memorial walk.

In spring 2023, the Sioux Sanatorium and Lakota Lodge (the original boarding school boys’ dormitory) were torn down.

All that remains of the Rapid City Indian Boarding School is the horse barn, the root cellar, unmarked graves and the memory of what once happened there.

“We’ve still had just enough power to reclaim what had been taken away from us,” Brown said.

External

Identification not yet made

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

Radio collaboration highlights importance of cooperation in a season of funding cuts for local media

A memorial in the Snow County Prison, now the United Tribes Technical College campus

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairwoman Janet Alkire tells crowd, ‘We’re going to rely on each other’