News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Young Native mother’s death sparks questions

Supporters stand outside the Pennington County Jail on Dec. 6, 2022. (Courtesy photo)

Supporters stand outside the Pennington County Jail on Dec. 6, 2022. (Courtesy photo)

In May of 2021, Abbey Lynn Steele gave birth to her first child, a baby boy.

A urine test showed methamphetamine in his system.

Steele, who turned 19 that month, also tested positive for meth.

The drug’s detection in the baby’s urine assured that Steele would not keep full custody under South Dakota law. Its presence in her system set in motion a series of events that defined the rest of her short life.

Instead of receiving a visit from a counselor or a trip to treatment, the young mother was charged with felony ingestion of a controlled substance. Some states criminalize drug ingestion, but South Dakota is the only state in the nation with a law that explicitly allows authorities to press felony charges that could result in prison time.

For well over a year, Steele, struggled to comply with the conditions of her pretrial release on that felony charge. On six occasions, she wrote letters to a judge to plead for another chance on a pre-trial sobriety program after missing drug testing appointments or missing court and landing in jail – a place she deeply feared, her family said.

“She’s very small, so she was always very scared of getting locked up,” said Maria Steele, Abbey’s older sister. “She didn’t like to go to the hospital, because she was afraid she’d get charged with ingestion again.”

On Nov. 16, 2022, for reasons that are under investigation, Abbey Steele’s heart stopped at the Pennington County Jail a few hours after an arrest on warrants for missed court appearances.

She’d given birth to her second child in an emergency cesarean section at a Rapid City hospital just five days earlier.

Paramedics were able to resuscitate Steele, but after two weeks on a ventilator and multiple MRI scans that indicated no prospect of life without the support of a machine, her family chose to pull the plug.

It wasn’t the way Maria had pictured saying goodbye to her sister.

Abbey had gone on a walk to buy a soda the day of her arrest and was walking back to Maria’s apartment when an officer began trailing her, Maria said. Abbey called her sister about it, then fled toward Maria’s apartment, where she was apprehended.

Maria took a video of the events inside her apartment, which shows Abbey on her knees being handcuffed and then being walked out by police.

“That’s my last memory of her, basically her getting dragged out of my house to her death bed,” said Maria Steele.

Days after Abbey’s death on Dec. 2, the Steele family and their supporters in the Native American community sent out a press release for a candlelight vigil outside the Pennington County Jail. They wanted answers on how Abbey died.

“Her death under the watch and authority of major institutions in Rapid City is an affront to common decency and basic human dignity,” the release said. “Abbey Steele should be alive today. Two children are now without their mother and have lost the opportunity to know her.”

Cries of “justice for Abbey Steele” heard at the vigil doubled as a plea for a re-examination of South Dakota’s approach to drug addiction. They also highlighted the impact of that approach on marginalized people, who struggle to see law enforcement as an arm of government with their best interests at heart.

Natalie Stites Means is a Rapid City community organizer who attended the vigil. She’s also a member of a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights advisory committee that recently released a report outlining maternal mortality and health disparities for Native women in South Dakota.

“We issued some demands,” Stites Means said. “Broadly, it’s ‘stop arresting, policing, surveilling and cataloging our people and calling that services.’”

Investigation ongoing

Representatives with the Rapid City Police Department and Pennington County Sheriff’s Office have declined to offer many details about the circumstances surrounding Abbey Steele’s arrest and detainment on Nov. 16, citing an ongoing probe by the state Division of Criminal Investigation.

An outside investigation is routine in cases of an inmate death or cases with questions about officer conduct.

“That evening, Abbey presented with medical symptoms and was transported to Monument Health via ambulance at approximately 8:32 p.m., where she was admitted,” wrote sheriff’s office spokesperson Helene Duhamel. “The Pennington County Sheriff’s Office received notification that Abbey died on December 2, 2022.”

On the police side, spokesman Brendyn Medina said an officer saw Abbey on Nov. 16, recognized her as a person with multiple warrants, and called out her name.

“Without any further actions by our officer outside of calling her name, Abbey decided to begin running from the officer,” Medina wrote in an email. “The officer observed her run into an apartment that ultimately did not belong to her. Not knowing her intentions, or even if she posed a danger to those inside, the officer followed her into the residence.”

Medina wrote that the arrest was “routine,” that there were “no indications of any need for medical attention,” and that “at no time did the officer ever have to use any force.”

“Regardless, this is an entirely tragic situation and the collective sympathies of the RCPD go out to a family and a group of friends that are now grieving the loss of a loved one.”

In Maria Steele’s video of the arrest, provided to South Dakota Searchlight, she can be heard saying, “I have Rapid City police inside my house right now. I did not tell him he could come in here.”

“That’s ’cause she came in here to avoid my arrest,” the officer says.

The video also shows Maria telling her young children to go upstairs and shuffling them out of the way of the commotion.

Abbey Steele is on her knees in handcuffs as the video begins. Within a minute, Abbey is on her feet and walking toward the door with the officer. Before they leave, a weeping Abbey can be heard saying “I love you so much” as she asks Maria for a hug.

“I’ve been having nightmares,” Maria said, recalling the arrest. “I hear her screams often in my head.”

Fear of punishment

No matter what the investigation into the arrest and detainment reveals, Abbey Steele’s supporters see her death as evidence of abject systemic failure, threaded through with historical significance for the tribal citizens of South Dakota.

To them, the state’s tough-love approach to drug use and addiction is an extension of generations of imbalanced treatment by a system that views Native Americans as projects to be fixed through force and coercion.

More than half the inmates in the state’s only women’s prison are Native. As of October 2022, a drug use or possession charge was the highest-level offense for half of all female inmates, regardless of race. The highest-level charge for 15 percent of inmates was ingestion.

It’s unclear how many of the women serving those drug sentences are Native American. The South Dakota Department of Corrections (DOC) keeps statistics on inmate offenses and inmate race and ethnicity, but DOC spokesman Michael Winder said the agency does not keep data on offenses by race.

“Your request was shared with our analytics division,” Winder wrote on Dec. 16 in response to South Dakota Searchlight’s Dec. 8 data request. “They have many requests to fulfill and your request is under review.”

Disparities in detention rates are similar inside the Pennington County Jail. On the morning of Dec. 15, 2022, for example, 322 of the inmates were Native American. The jail’s capacity is 587. Native Americans make up 11 percent of Pennington County’s population, according to census data.

Beyond placing additional pressure on prison staff and facilities already overwhelmed with drug possession crimes, Stites Means said, South Dakota’s felony ingestion law creates a climate of fear around pre- and postnatal care whose ripple effects put children and mothers at long-term risk.

The 2021 report on maternal health that Stites Means worked on outlines some of the reasons for that. The study group heard from doctors who said Native women are more likely to be drug-tested in hospitals – with or without a patient’s consent.

One doctor said Native women “often feel stigmatized, stereotyped and dismissed by the medical system, which makes them hesitant towards accessing necessary health care.”

Several doctors told the commission that mandatory reporting of drug use and the criminal charges that can follow it act as barriers to care. One said it’s impossible for a doctor to forge genuine relationships with drug users “if they fear that they’re going to be thrown into jail if they actually open up.”

With that backdrop, Stites Means said, Abbey Steele’s story stands as tragic proof that fears of sanction for seeking health care are firmly rooted in experience.

The report from the civil rights advisory committee showed that maternal death rates for Native women are two and a half times higher than rates for White women, Stites Means said, and “felony ingestion is a part of that.”

Drug addiction colored Steele’s life

The report also noted that rates of drug use before and after pregnancy are three times higher among Native women than White women, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Abbey Steele’s life reflected that reality long before she gave birth to her son.

Her mother, now the guardian of Abbey’s children, struggled with addiction for years before finding her footing.

Maria and Abbey had different fathers, neither of whom were around. Like her younger daughter, their mother was charged with felony ingestion in South Dakota.

“Me and Abbey were all we had for our whole lives growing up,” Maria Steele said. “Our mom was in and out of prison.”

Like her daughter, Abbey’s mother gave birth at a young age. Abbey was born three years after Maria, in Rapid City, but the Oglala Lakota family spent many of their early years in Bismarck, North Dakota. Abbey returned to the Rapid City area at age 10, when her mother lost custody based on North Dakota charges.

Abbey played flute and volleyball in North Dakota, and continued doing so in middle school in Rapid City. She spent her high school years in Sturgis.

Through it all, Maria said, Abbey maintained a spirit of loyalty that outshined others in her family. She stuck up for the people she loved.

“Abbey was a firecracker,” Steele said. “She was very feisty. If someone said something and she didn’t like it, she wasn’t afraid to tell them how she felt.”

It took years of incarceration, treatment and family separation for the sisters to be reunited with their mother, whose criminal history in South Dakota mirrors that of her younger daughter in many ways – drug use without violence, stumbles on probation that led to incarceration, pleas for mercy and promises to improve.

At one point, their mother wrote a letter explaining that her failed drug test on probation was a relapse after 268 days clean in drug court.

She would go on to serve about a year of a two-year ingestion sentence at the South Dakota women’s prison.

“She was taken from our lives for a very long time,” Maria said. “I do think that knocked some sense into her, because her whole life changed when she came out.”

Like her mother, Abbey found herself wrapped up in drug use as a teenager. She was quick with a joke to lighten the mood, Maria said, but she also struggled with trauma and used drugs to help herself cope.

She wasn’t a violent or dangerous person, Maria said.

“Abbey was an addict and treated like a criminal,” she said.

Prior to her first pregnancy, Abbey’s criminal record had one ticket: for driving without a license. The first of her other five charges originated in the maternity ward at Monument Health.

Stumbles through the system

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that health systems avoid drug tests without consent, over concerns that the tests stigmatize patients and discourage them from seeking health care.

Monument, the Rapid City-based health system, declined to comment on Abbey’s case specifically, but Maria said Abbey did not consent to the May 2021 drug test that would ultimately lead to Abbey’s felony ingestion charge.

The RCPD needs consent or a warrant to obtain a second urine test for charging purposes after an initial test by a hospital, Assistant Chief Scott Sitts said, but he declined to offer further details on Steele’s specific situation at the time, citing the ongoing investigation.

The immediate effect of the positive test from 2021 was a loss of full custody. Maria and her mother signed an agreement with the Department of Social Services, promising to help watch over the boy.

Abbey understood why, Maria said, but the loss had a long-term impact.

“She was just broken,” Maria said. “She wasn’t herself.”

The drug test used in the criminal case was administered on May 27, 2021, and after a standard delay to process evidence, Abbey was indicted by a grand jury on the ingestion charge on July 14, 2021.

Abbey was served a warrant and arrested on the charge in September. She was released on bond shortly thereafter. The following month, she was arrested for driving under the influence. A few weeks after that, she was charged with impersonation to deceive law enforcement for giving a fake name to an officer.

In each case, she was released into the 24/7 sobriety program on the condition that she appear for random urinalysis screenings, but she missed several of them. The 24/7 program began in South Dakota as a pretrial condition for repeat DUI offenders, who would appear at the county jail for a breathalyzer test twice a day. The program has since expanded to include alcohol monitoring bracelets, drug patches and random urinalysis tests. Defendants pay for each form of monitoring.

Beyond missed 24/7 appointments, Abbey Steele missed nine court appearances for status hearings and motions in her pending cases from October 2021 through this November.

It wasn’t easy to make her court appearances and drug tests, Maria said.

For a time, Abbey was living on the streets with her boyfriend, but she kept working at Wendy’s and delivering diapers and clothes for her son. The boyfriend, who is the father of her children, didn’t get along with the rest of the family, which led to periods of estrangement. The two “were not good for each other,” Maria said, but they loved each other deeply.

Even when she had a place to stay and the couple were at peace with the rest of the family, Abbey didn’t have reliable transportation.

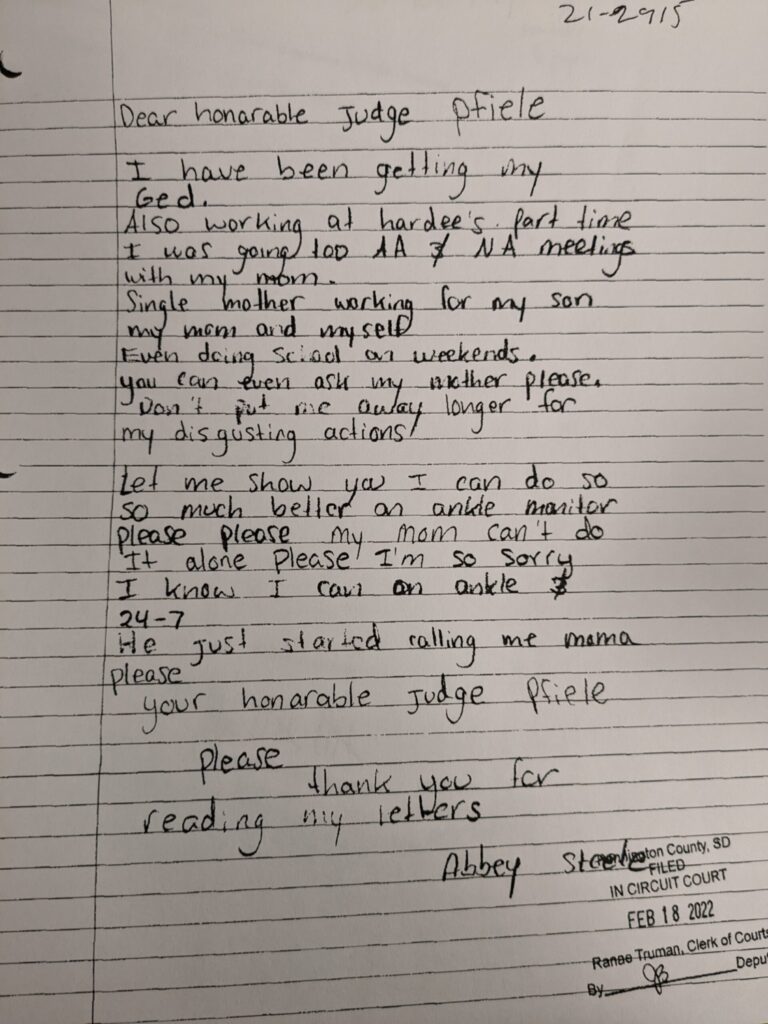

She was detained on warrants several times. On six occasions, beginning in February of 2022, she wrote letters to Judge Jane Wipf Pfeifle asking for another chance on 24/7. She mentioned her work at Wendy’s, illness in her family, her hopes for her children, and the strength of her mother and sister as a support system for staying sober. In one letter, she talked about picking up additional hours at Hardee’s and attending Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

Her mother needed help with her son, Abbey wrote in February, shortly after the boy hit a developmental milestone.

“He just started calling me mama,” she wrote.

Sobriety was her goal, she’d write later.

“If given this chance, I will go to 24-7 and behave in a well manner this time because I want my unborn baby to have a bright future, as both my kids mean the world to me,” Abbey wrote over the summer.

Punitive approach scrutinized

To Libby Skarin of the American Civil Liberties Union of South Dakota, Abbey’s case is reflective of the cascade of sanctions that trail those who struggle with substance abuse in South Dakota.

People trying to kick highly addictive drugs are highly likely to use again – often more than once – before long-term sobriety takes hold, Skarin said. Criminalizing each predictable stumble, she said, places more pressure and stress on drug users, which makes South Dakota’s ingestion law counterproductive.

“When you apply a felony-level penalty to someone and charge them with a crime that is related to addiction, you are starting in motion a series of consequences that the person might never escape from in their life,” Skarin said.

Thus far, the Legislature has been unwilling to change the law.

The most recent attempt came from Sen. Mike Rohl, a Aberdeen Republican, in 2021. Supporters of the bill pointed out that South Dakota incarcerates more drug users per capita than any other state, among other drug-related statistics.

Rohl’s bill would have reduced ingestion from a felony to a misdemeanor. It failed in committee on a 5-2 vote. Rohl and Republican Sen. Art Rusch, a retired judge from Vermillion, were the lone “yes” votes.

The ingestion law also came under fire in 2017, when an Argus Leader investigation revealed that some defendants had been forced to give urine samples through unwilling catheterization. A federal judge struck down the forced collection of urine in 2020 after a lawsuit by the ACLU.

Law enforcement officials in the state argue that the ingestion law holds accountable drug users who would otherwise avoid treatment. Without it, they say, their hands would be tied in battling methamphetamine, South Dakota’s number one controlled substance in terms of arrests.

Officials also point out that ingestion carries a presumption of probation, meaning that diversion is expected before a prison sentence is levied in an ingestion case.

The law is also a tool for negotiation. Abbey Steele’s mother was charged with both drug possession and ingestion in 2013. Her plea deal kept the ingestion charge, and she took the bargain.

Diversion is part of the charging calculus for Interim Pennington County State’s Attorney Lara Roetzel and her deputies. Not all meth-born baby cases result in charges, she said this week.

“There are a multitude of factors we take into account when charging this type of case,” Roetzel wrote in an email. “Some of these include prior history of the mother, cooperation with the Department of Social Services, prior rehabilitation efforts, and potential danger to the community and to the person. Some of these cases end up in diversion efforts, others in charges, some in no charges at all. It is important not to take a cookie-cutter approach to prosecution.”

Family, supporters: South Dakota system failing

Stites Means sees more than a legal debate. She sees a continuation of a history of racism in South Dakota, with shades of the “kill the Indian, save the man” belief that drove the forced removal of Native children and placement in boarding schools during the 1800s.

Harsh penalties that statistically hit Native communities harder than White communities are a sign that the state’s criminal justice system has no interest in addressing discrimination against minorities, or the damaging effects of family separation, she said.

“I do think it’s warlike, and I think it’s genocidal, and I’m not going to compromise on that,” Stites Means said. “It’s factual.”

Stites Means also said South Dakota’s drug policies do not reduce drug use, access to drugs, or public safety.

“Nobody’s safer for any of this,” she said.

Near the end of Abbey Steele’s life, the last time she tried to get a spot in a treatment center for mothers and newborns, her sister Maria said, the line was too long. They were told that too many women leaving the prison were ahead of her.

“Abbey was very open to learning and getting help,” Maria said.