The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

Two sisters fight for freedom in ‘miscarriage of justice’

Miles Morrisseau

ICT

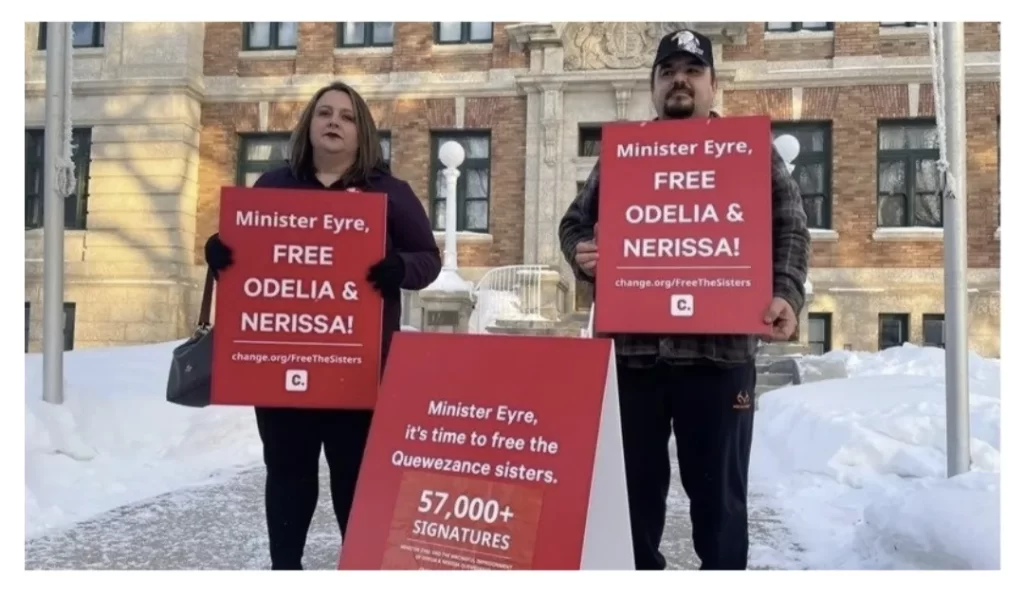

The four Quewezance sisters reunited for the first time in 18 years on Jan. 18, 2023, outside the Yorkton courthouse in Saskatchewan , Canada. The two sisters on the back row, Nerissa, left, and Odelia, right, are petitioning the Canadian government to overturn their conviction 30 years ago of a murder that another man confessed to committing. They were joined at a hearing on their case by two other sisters, Zerlina, left, and Bonnie, right, who wore ribbon skirts in celebration of the reunion. (Photo courtesy of Nicole Porter)

The First Nations women were convicted despite another man’s confession in what an official calls ‘Indigenization of Canadian corrections’

The cold of the Canadian prairie in mid-January couldn’t chill the long-awaited reunion of the Quewezance sisters.

Standing on the snowy steps of the Yorkton Court of King’s Bench in Saskatchewan, the four sisters huddled close, with smiles and hugs. Two sisters wore ceremonial ribbon skirts in support of the cause.

It had been about 18 years since they’d been together, and three decades since they’d had any real hope that Nerissa and Odelia Quewezance would be released from prison for a murder they insist they didn’t commit.

“It is shocking that something like this is happening right here in Canada,” Nicole Porter, a criminal justice consultant who is pushing for the sisters’ release, told ICT. “I don’t think a lot of the people who live here realize that this stuff happens. People think, ‘Oh, different countries, maybe in the U.S. … but not here.”

The decades-old murder case in Saskatchewan, however, has brought new attention to racial inequities in Canada’s criminal justice system as the sisters edge closer to possible exoneration for a murder someone else has confessed to committing.

Their convictions are under review by Canadian Justice Minister David Lametti, who could throw the murder conviction out altogether for a lesser charge or refer the case back to a Saskatchewan court for reconsideration.

“There may be a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice has occurred,” according to a letter sent by the minister’s office to lawyer James Lockyer, founder of Innocence Canada who is representing the Quewezance sisters.

The sisters, from the Keeseekoose First Nation, have drawn support from leaders in the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, who have formally petitioned the Canadian government, and other rights organizations.

The case has also inflamed tensions about the inequities in Canada’s criminal justice system. Indigenous women make up 50 percent of the women in federal prisons, and a string of cases has drawn attention to the disparate handling of Indigenous people in Canada’s courts.

No one denies that the system is broken, particularly in Saskatchewan, where Indigenous peoples represent 75 percent of all people incarcerated in provincial and federal institutions.

“Systemic racism is an unfortunate reality in Canada’s justice system,” according to a statement to ICT from Diana Ebadi, press secretary for Lametti. “The Minister of Justice has been clear: reducing the over-incarceration of Indigenous People is a key priority for him and the federal government.”

Indigenous women hit a dubious milestone in April, when they reached 50 percent of the incarcerated women in the federal prison system, according to Canada’s Correctional Investigator Dr. Ivan Zinger.

Of the women classified as maximum security, such as the Quewezance sisters, almost 65 percent are Indigenous, Zinger said.

“Unfortunately, these are not new developments in federal corrections,” Zinger said, in releasing an annual report in June. “My office and others have been reporting on the Indigenization of Canadian corrections for years. A deeper dive into the situation uncovers that this over-representation is largely the result of systemic bias and racism.”

‘Miscarriage of justice’

Jason Keshane, a cousin to the sisters, admitted on the witness stand that he killed 70-year-old farmer Anthony Joseph Dolff on Feb. 25, 1993, in Kamsack, Saskatchewan, not far from the Keeseekoose First Nations.

Keshane, who was just 14 years old at the time, had joined Nerissa, then 18, and Odelia, then 20, at the man’s home for a night of partying. Things got ugly after Dolff propositioned the women, Keshane told APTN News in 2020, and he stabbed and strangled the man, then hit him in the head with a television.

He had already testified at trial that he had killed Dolff, but the judge warned jurors to beware of testimony from unworthy witnesses. The jury found both women guilty of second-degree murder.

Keshane pleaded guilty to second-degree murder. Because of his young age, however, he was sentenced to four years, including 2 ½ years in a juvenile facility.

Odelia told APTN that the man’s advancements triggered memories of abuse she had suffered at residential school, which she and her sister were forced to attend. Dolff had worked as a maintenance man at the school the girls attended.

Since the conviction, Odelia’s partner has pushed ceaselessly for her release, eventually catching the attention of the late David Milgaard, who is perhaps Canada’s most famous wrongly convicted person. Milgaard, who spent more than 20 years in prison for a rape and murder he didn’t commit, brought in Porter and Innocence Canada, with whom he’d worked.

Porter said she conducted an independent forensic analysis of the case, poring over investigative reports and trial transcripts.

“I came to the same conclusion that everybody had,” she told ICT. “There was a gross miscarriage of justice in this case. There was no physical evidence whatsoever tying these women to the murder. And what’s unique about this case, is that there was a confession, not only at the time of the trial, but years later on national television.”

The sisters are now limited in their ability to speak about the case, but they have always maintained their innocence. The hearing in January drew supporters from across Canada.

“They had a tremendous amount of support at the hearing,” Porter said. “There were family members, friends, other members of Innocence Canada (aside from their legal team), and advocates who traveled from all over the country to be there, including myself.”

Systemic racism

The Canadian justice system has been accused of inherent bias against Indigenous people and in favor of White people since perhaps its inception. It’s a problem that has worsened in recent years.

Recent numbers gathered by Statistics Canada show that Saskatchewan has the highest incarceration rate in the country, with Indigenous peoples representing 75 percent of all the people incarcerated in provincial and federal institutions.

The numbers do not surprise advocates.

“Saskatchewan is known to be very racist, systemically,” Porter said. “Instead of having any progress or having any government official reach out to us and acknowledge the harm done or offer any attempts at reconciliation to make this right, they’re doing the opposite.”

In a high-profile case last year, award-winning author Dawn Walker, who uses the pen name Dawn Dumont, went on the lam with her son, saying after she was captured in the United States that the failures of the Saskatchewan justice system had fueled her flight.

“I left Saskatoon because I feared for my safety and that of my son,” she said. “I was failed by the Saskatchewan justice system, the family law system and child protection.”

The flight came amid a custody dispute with the boy’s father, who is not Indigenous.

“I am fighting systems that continuously fail to protect me as an Indigenous woman, and protect non-Indigenous men,” Walker said. “Saskatchewan and the systems within have failed Indigenous people since colonization.”

Perhaps one of the most egregious examples of the Canadian system favoring non-Indigenous men is the case of Carney Nerland.

On Jan. 28, 1991, Nerland, a professed white supremacist and a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was convicted of manslaughter in the death of Leo Lachance, a member of the Big Cree First Nation.

Lachance, who was unarmed, was shot to death on the streets of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Nerland was convicted of manslaughter, and served three years of a four-year sentence.

The case drew national attention to the existence of hate groups in Canada. The Klan has a nearly 100-year history in Canada.

In another case in 2004, an inquiry into the death of 17-year-old Neil Stonechild by Justice David H. Wright revealed the practice of “Starlight Tours” by the Saskatoon police.

The teenage member of the Saulteaux First Nation – and a one-time bantamweight provincial wrestling champion – was under-dressed for the minus-zero temperatures when police dumped him on the edge of town to walk back after he was picked up for intoxication.

He was found dead the next day of hypothermia, with one shoe missing. The officers were fired but served no time.

“I am satisfied that [the officers] had adequate time between the Snowberry Downs dispatch and O’Regan Crescent dispatch to transport Stonechild to the northwest industrial area of Saskatoon,” the judge concluded.

Another case involved 22-year-old Colten Boushie, from Red Pheasant Cree Nation, who was shot in the back of the head in 2018. Boushie and his friends had driven onto the man’s property and were parked, unarmed. The shooter served no time.

David Taylor from Canada’s Department of Justice told ICT in an email that inmates do not necessarily serve time in their home districts, but he acknowledged the disproportionate sentencing of Indigenous people.

“It remains a fact that Indigenous people are overrepresented versus their percentage of the population,” he said “That is something our government is working to address.”

What’s next

For now, however, the two Quewezance sisters are in limbo. Odelia has been released on day parole but Nerissa remains in federal custody at the Fraser Valley Institution for Women in British Columbia.

A decision is expected by mid-February on their request for conditional release, with a decision from the justice minister to come some time later.

The Department of Justice’s Criminal Conviction Review Group is now reviewing the women’ case, and will advise the justice minister on an appropriate remedy, Ian Mcleod, a spokesperson for the Department of Justice, told ICT in an email.

Porter said she appreciates the Canadian government’s review of the case but said it won’t get the sisters out quickly.

“That can take two years,” she said. “They can’t stay there another two years. That’s just not right.”

External

Identification not yet made

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

Radio collaboration highlights importance of cooperation in a season of funding cuts for local media

A memorial in the Snow County Prison, now the United Tribes Technical College campus

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairwoman Janet Alkire tells crowd, ‘We’re going to rely on each other’