Oglala Sioux Tribe denounces Defense Department’s refusal to revoke soldiers’ Wounded Knee medals

President Frank Star Comes Out calls decision ‘despicable’

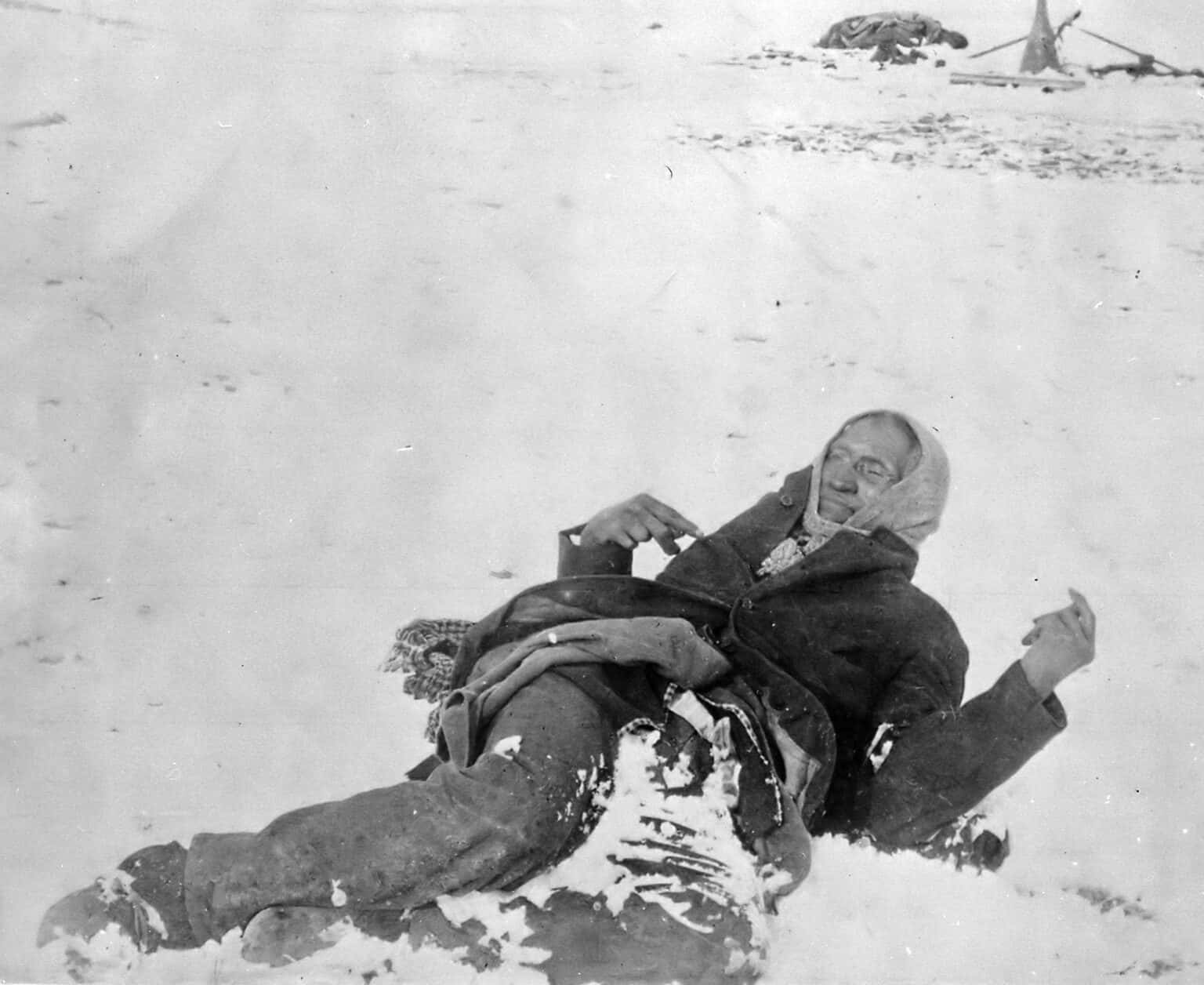

Miniconjou Chief Spotted Elk (aka Big Foot) lies dead in the snow after the massacre at Wounded Knee, January 1, 1891. (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/unknown photographer)

The U.S. Army’s 1890 massacre of an encircled group of Natives has been brought to light again, after Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced that 20 soldiers involved in it would keep their military honors. Those soldiers include Mosheim Feaster, who was awarded for “extraordinary gallantry,” Jacob Trautman, who “killed a hostile Indian at close quarters,” and John Gresham, who “voluntarily led a party into a ravine to dislodge Sioux Indians concealed therein.”

Calls to revoke the soldiers’ medals of honor gained momentum in 1990 after the 100th anniversary of the Wounded Knee massacre, with the U.S. Congress issuing a bipartisan resolution calling it a tragedy. Pressure continued to build through the decades on the White House and Defense Department, even as some members of Congress stalled discussions and blocked legislation.

In July 2024, President Biden’s defense secretary, Lloyd Austin, convened a panel to review the medals of honor that were awarded for actions “related to the engagement” at Wounded Knee Creek. The panel did not recommend revoking them, but Austin hadn’t made a final decision on the matter before leaving office earlier this year.

For the Oglala Lakota people, the Wounded Knee incident remains a dark chapter in their history, with a memorial ride held every December to commemorate those who were killed.

‘The most abominable military blunder’

On Dec. 28, 1890, near the end of the era known as “The Indian Wars,” U.S. soldiers intercepted a group of roughly 350 Lakota — many women and children — and rounded them up to be kept under the armed watch of the 7th Cavalry. The same cavalry had suffered a devastating loss 14 years earlier at the Battle of Little Bighorn, when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer fatefully engaged a force of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne, which decimated the soldiers.

But the Lakota standing in the snowy field circled by Hotchkiss guns weren’t warriors. They were weary Natives led by Chief Spotted Elk (called Chief Big Foot by soldiers).

The next day, soldiers attempted to disarm the Natives. Accounts vary as to what exactly happened, but after a shot rang out, the soldiers fired directly into the largely unarmed mass of elders, women and children. In the confusion, U.S. soldiers were both hit by friendly fire and fired on by the few Lakota with guns, resulting in the death of 25 soldiers.

An examination of the carnage revealed that U.S. soldiers had chased down and killed people as they fled. Just over four dozen Lakota survived, either escaping or being sent by wagon to the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Medals of honor

The following year, the U.S. Army awarded 20 Congressional Medals of Honor to soldiers who’d engaged the Lakota at Wounded Knee, in spite of what was a catastrophic failure of containment and deescalation on their watch.

Notable brass of the time, including Major General Nelson A. Miles, condemned the Wounded Knee incident as “the most abominable military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children.”

The current defense secretary doesn’t see it that way.

On Sept. 25, ahead of the 135th anniversary of the Wounded Knee massacre, Hegseth, who leads the newly branded Department of War, announced that the Wounded Knee medals would not be revoked.

“We’re making it clear that [the soldiers] deserve those medals,” Hegseth declared in a video posted to X, adding,“Their place in our nation’s history is no longer up for debate.”

‘A stain on the conscience of this nation’

Hegseth’s announcement brought an angry rebuke from Oglala Sioux Tribal President Frank Star Comes Out, a descendant of Chief Spotted Elk.

“These Medals of Honor remain a stain on the conscience of this nation,” Star Comes Out said in a press release the following day. “Until they are revoked, the United States cannot claim to stand for honor, integrity, or justice. We will not rest — not today, not tomorrow, not ever — until the truth is acknowledged and this national disgrace is corrected; our story must be told for generations to come.”

Oglala Sioux Tribe families hold annual memorials in December to honor the victims killed at Wounded Knee, and, according to the tribe, their descendants have served honorably in every U.S. conflict from World War I to Afghanistan.

Star Comes Out, a Marine veteran who served in the Gulf War and Mogadishu in the 1990s, told Buffalo’s Fire he takes military service and honors seriously.

Of Hegseth’s decision, he said, “It’s despicable, untruthful, and insulting to our people. This is history. Our people are traumatized. We have to live with that. And I keep saying this every time I go to Washington, when I advocate for my tribe and tribes nationwide, we were never dealt a fair hand.”

Star Comes Out vowed to keep fighting to get the medals from Wounded Knee rescinded to rectify the dishonor inflicted on his people. “We always get the bad end of the deal,” he said. “It’s time that changes.”

The National Congress of American Indians has also issued a statement condemning Hegseth’s announcement, urging Congress to revisit the medals “so that the nation’s highest honor fulfills its namesake by reflecting courage, not cowardice and cruelty.”

Brian Bull (Nez Perce Tribe)

Senior Reporter

Help us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.