Reporters’ Notebook: The year that was

Buffalo’s Fire reporters reflect on their biggest stories of 2025

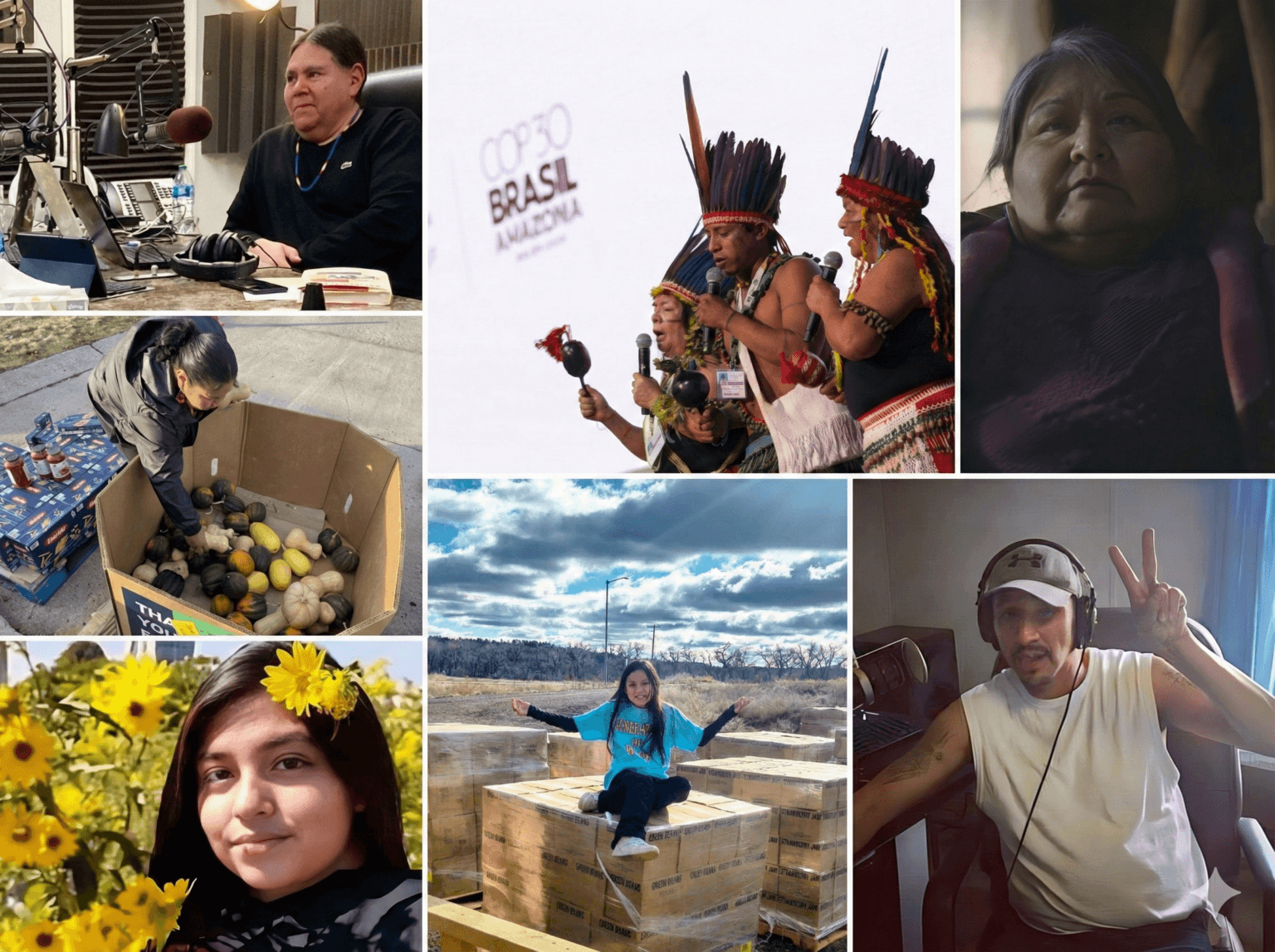

Clockwise: Indigenous dancers at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, Monday, Nov. 10, 2025. (UN Climate Change/Kiara Worth); Elaine Miles in HBO Max’s series “The Last of Us.” (Photo courtesy of HBO); Nathaniel Iron Road, undated. (Screen grab: Facebook); Anna Fishinghawk, Northern Cheyenne Reservation, Montana, Tuesday, Nov. 25, 2025. (Generations for Hope/Tonah Fishinghawk-Chavez); Leticia Jacobo, 2025. (Photo credit: Ericka Burns); Melanie Moniz, Bismarck, North Dakota, Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2025. (Buffalo’s Fire/Gabrielle Nelson); “Native America Calling” host Shawn Spruce, April 25, 2025. (Photo credit: Art Hughes)

In a year defined by systemic upheaval and political friction, Buffalo’s Fire reporters look back at the defining stories of 2025, from the frontlines of federal immigration enforcement to the grassroots fight for environmental and social justice.

These are the stories that defined our year.

Brian Bull

The year 2025 was one of upheaval and uncertainty, and probably the confrontations between ICE and Native people were the most alarming. Within the first few weeks of President Trump’s crackdown on immigration, tribes across the U.S. were hearing of their citizens being stopped and questioned by federal agents. Besides my commentary on feeling the need to get my first photo tribal ID ever, I reported on Leticia Jacobo, a Native woman who was set to be released on Nov. 11 from the Polk County Jail in Des Moines, Iowa, but instead was held on an ICE detainer after a clerical error supposedly caused her to be confused with another inmate who shared her last name.

Earlier in November, actor Elaine Miles was confronted by a group of men claiming to be ICE, who said her tribal ID was “fake” and appeared confused or defiant when she asked them if they had a warrant. Both Jacobo and Miles saw these incidents as examples of racial profiling, even as officials with the Department of Homeland Security have denied this.

Another concerning national trend was the rescission, where Congress abided by President Trump’s push to clawback more than $1 billion in funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Driven largely by the Republican Party’s right-wing ideology that NPR and PBS programs are “woke,” the push actually has hurt operations at tribal and community stations that provide cultural programs and timely weather updates. While some of the larger stations have enjoyed increased listener support in defiance of the rescission, those in rural areas especially are facing severe cuts in staff and operating budgets. Some Republicans, including U.S. Senator Mike Rounds of South Dakota, have pointed to a last-minute workaround that’ll give tribal media access to $9.4 million in funding, but who qualifies — and for how much — remain unanswered questions.

Gabrielle Nelson

Environment reporting this year was very doom and gloom, as it typically is. With the Trump administration slashing climate funding and pushing for the expansion of fossil fuels, renewable energy projects faced major setbacks. But where the federal government is lacking, Native communities have been stepping in to support each other. During coverage of United Tribes’ Tribal Leader Summit in early September, I reported on funding cuts to tribal solar projects. As a result of such cuts, programs including the Midwest Tribal Energy Resource Association and Indigenized Energy are looking to tribal funding to keep their projects moving forward.

In November, when the government shutdown delayed SNAP benefits, Native organizations and tribes stepped in, providing food assistance to those in need. United Tribes Technical College student Tonah Fishinghawk raised $12,000 in food assistance for the Northern Cheyenne Tribe in Montana, all five tribes in North Dakota and food banks at UTTC and the Sacred Pipe Resource Center in Bismarck.

Indigenous communities and organizations also demanded to be heard in global climate talks. At the 30th annual Conference of Parties, or COP30, in mid-November, world leaders gathered to set climate goals in Belém, Brazil, the gateway to the Amazon — which is home to 1.5 million Indigenous people. Even with the United States not in attendance, U.S.-based Indigenous organizations, including the Indigenous Environmental Network, advocated to increase direct climate funding and limit fossil fuels. Time and again, globally and locally, Indigenous communities are proving themselves to be stewards of the environment and their communities.

Jolan Kruse

It has been an honor to spend 2025 helping to tell the stories of those affected by the MMIP crisis. This year, I have been able to expand MMIP coverage of local communities by reporting on cold cases where loved ones are still seeking justice. One of these cases — that of Nathaniel Iron Road — raises questions about an ambulance service’s failure to respond and whether federal agents are still investigating it, as a mother and four children are left to mourn year after year without answers. The Native community continues to demand justice for their missing and murdered people and continues to say their names.

I have also brought coverage to cases as they’ve unfolded. In October, I reported on Spirit Lake citizens searching for two missing loved ones, Isaac Hunt and Jemini Madeline Posey. I wrote about Posey trying to leave an abusive relationship prior to her disappearance. In November, Isaac Hunt’s remains were found. Shortly after Isaac was found, Posey’s boyfriend, D’Angelo Hunt, who is also Hunt’s brother, was charged in connection to Isaac’s murder and the voluntary manslaughter of “J.M.P.,” believed to be Posey.

I have also been able to report on the community’s response to MMIP and the need for solutions. In my article about Native advocates calling for the return of the groundbreaking Not One More report, I got to highlight its importance for addressing areas for improvement in federal, state and local resources. Despite its potential to change communities, it was scrubbed from the Department of Justice website following an executive order from the Trump administration. I found it powerful to report on the strength of those who call for its return and who advocate for a better future.

Buffalo’s Fire

Location: Bismarck, North Dakota

See the staff pageHelp us keep the fire burning, make a donation to Buffalo’s Fire

For everyone who cares about transparency in Native affairs: We exist to illuminate tribal government. Our work bridges the gap left by tribal-controlled media and non-Native, extractive journalism, providing the insights necessary for truly informed decision-making and a better quality of life. Because the consequences of restricted press freedom affect our communities every day, our trauma-informed reporting is rooted in a deep, firsthand expertise.

Every gift helps keep the fire burning. A monthly contribution makes the biggest impact. Cancel anytime.